Nestled in the picturesque village of Ardmore, County Waterford, lies a curious relic of Ireland’s ancient past – the Cloch Daha. This mysterious stone, whose name may mean “the stone of Daghdha” or simply “the good stone,” has captivated locals and visitors alike for generations.

A Stone Shrouded in Secrecy

The Cloch Daha’s history is as intriguing as its appearance:

- Once deliberately buried by clergy to end “decadent ceremonies.”

- Rediscovered and moved to the grounds of Monea House

- Now rests in a private garden

A Peculiar Shape

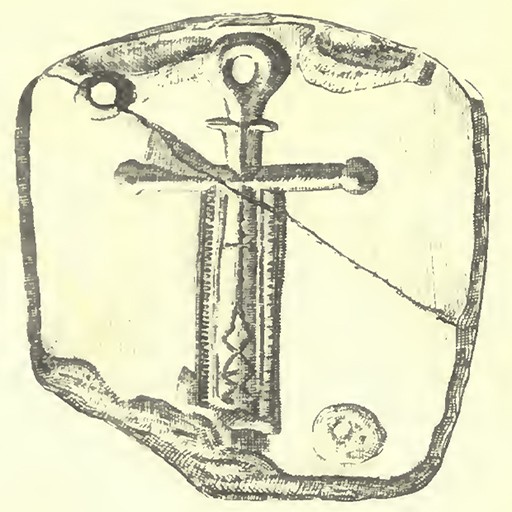

This limestone block, roughly 2 feet long and 18 inches wide and deep, features:

- An oval trough-like shape, possibly an ancient pagan bullan or rock basin

- A central hole, crucial to its mysterious rituals

Rituals of Romance and Mischief

On Ash Wednesday, the stone came alive with a curious custom:

- Young bachelors inserted a wattle topped with tow into the central hole

- Unmarried maidens were gathered to dance around the stone

- The ceremony ended with girls being pulled through the village on wooden logs

Theories and Speculations

Scholars and locals have long debated the stone’s true purpose:

- Some connect it to pagan rites or the god Dagda

- Others suggest it might be the plinth of an ancient cross

- Local lore claims it was used as a communal dye bath for homespun yarn

A Glimpse into the Past

Richard P. Keating, a resident, shared his grandfather’s recollections:

- The stone was originally buried in the “Faiche,” a common area near the shore

- It was moved to Monea House by Mr. Odell to protect it from the encroaching sea

Today, the Cloch Daha is a testament to Ardmore’s rich and mysterious past. As you explore this charming coastal village, watch for this hidden gem – a tangible link to ancient rituals and forgotten ways of life.

Citations:

[1] https://www.ardmorewaterford.com/the-cloch-daha/

Maidens Being Dragged Through Ardmore Village

Go off the regular heritage trail on Ireland’s Ancient East, and you may be lucky enough to discover some of the hidden artifacts in Ardmore.

The clergy deliberately buried one lesser-known famous stone at Ardmore and is now visible if you know where to look.

It was hidden probably to put an end to its decadent ceremonies. It must also be classed among relics connected with rites of days long gone by.

It was called the “Cloch-Daha,” which is said to signify “the stone of Daghdha”

It was about two feet long by eighteen inches in breadth and the same in-depth, hollowed into an oval trough-like shape, probably an old pagan bullan or rock basin. Its centre was pierced by a hole, in which, on Ash Wednesday, the young unmarried men of the village inserted a wattle, on the top of which they tied a quantity of tow. They then brought with them all the unmarried maidens they could muster from the village and vicinity and made them dance round the “Cloch-Daha,” holding the pendant tow, and spinning it whilst dancing. The ceremony terminated by the young men dragging the maidens through the village seated on logs of wood.

The above was taken from TRACES of the ELDER FAITHS OF IRELAND – A FOLKLORE SKETCH BY W. G. WOOD-MARTIN, M.R.I. A. (1902).

————–

In 1903, Notes on the antiquities of Ardmore Thomas Westropp discusses the Cloch Daha

“In the lawn of Monea House lies a remarkable stone resembling a rude cross base. It is 38 1/2 inches long, 18 inches, and 24 inches wide. In the centre is a hole, but, instead of being the usual oblong mortice or socket, it is rather oval, tapering down to a cup with a hole below. It is called the “cloche Daha” understood as “the good stone” by some connected to pagan rites, and with the Dagda by others. Brash gives a curious account, which he describes how a wooden rod or pole used to be set into it and crowned with a tow on Ash Wednesday. The youth of the village would dance around it, and drag old maids into the dance, afterward drawing them through the street, seated on logs of wood. Owing to the scandalous meaning attached to these rites, they were put down, and the stone removed and buried. He suggests that it may be the traditional stone marked by Declan’s head, but also equates it with the “Bod an dagga” near Ballymote and the “Bod Fheargais” at Tara.”

We include an extract from Parish of Ardmore and Grange written in 1912, which outlines some interesting facts about the

In the grounds of Monea House, Ardmore, is a dressed block of limestone, known as

, in which Marcus Keane and other fanciful people see an object once connected with Phallic or other pagan worship. This is apparently the plinth of an ancient cross and the mortise for the reception of the shaft came, in a later and less reverent age, to be used as a dye bath —hence the modern name. Allusion to the cross suggests the observation that in the parish are places called, respectively, Crossford (in Irish)

, in which Marcus Keane and other fanciful people see an object once connected with Phallic or other pagan worship. This is apparently the plinth of an ancient cross and the mortise for the reception of the shaft came, in a later and less reverent age, to be used as a dye bath —hence the modern name. Allusion to the cross suggests the observation that in the parish are places called, respectively, Crossford (in Irish)

and

(Aodh’s Cross)—so named, presumably, from Termon crosses marking the limits of St. Declan’s sanctuary lands. On the townland of the same name stand the rather insignificant remains of the ancient church of Grange, called also Lisginan.

——————

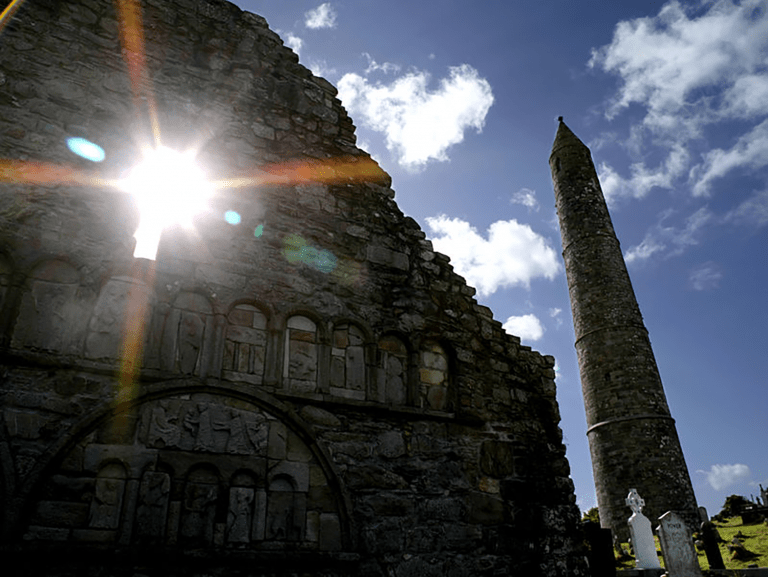

In another extract from I.T.A. Topographical and General Survey 1942

“Cloch Datha on the lawn of Colaiste Deuglain may be seen at any time by visitors. The Round Tower, Cathedral, and Beannachain are in the charge of the Office of Public Works. No admission charge.”

I remember the explanation that my Grandfather , Richard P. Keating, gave me about the CLOCH DATHA which is now in the private front garden of Mr Dan McNamara, In fact it has not been moved very far from where I first remember it. That had been on the front lawn of long demolished Monea House, since when the late Dr McNamara had his house built there on that very site.

My Grandfather told me that it had been buried in the “Faiche”, which was an area of common land in front of where the stormwall was built in the late 1800s. He said that he remembered having been told by elderly villagers ,when he first saw the hollow stone in it’s present location, that it had been buried on the orders of the clergy as it had associations with pagan rites and phallic worship. (We cannot assume that the clergy referred to were Roman Catholic) He was also told that Mr Odell had taken it for preservation to the grounds of Monea House when it’s survival was endangered by the encroaching sea.

I have also read that it had been used as a “basin” for the dying of the homespun yarn of the people of the village but I wonder if this was so Co-operative a form of manufacture and what necessity there would have been to have a communal basin for this purpose ?