Step back in time to 1642, when Ardmore’s iconic Round Tower and castle became the stage for a dramatic episode in Irish history. This little-known siege, overlooked by many historians, offers a fascinating glimpse into a turbulent era that shaped Ireland’s destiny.

The Setting

Picture Ardmore in the midst of the Irish Confederate Wars:

- The Round Tower, already ancient, stands as a silent sentinel

- A now-vanished castle guards the eastern approach to the church

- Tension fills the air as opposing forces converge on this coastal village

The Siege Unfolds

In August 1642, Lords Dungarvan and Broghil set their sights on Ardmore:

- A formidable force of 100 soldiers defends the castle and tower

- The attackers bring a culverin (a type of early cannon) to breach the defenses

- The Round Tower becomes an unexpected fortress, housing 40 men

A Battle Against Time and Stone

The siege proves more challenging than anticipated:

- Defenders utilize the tower’s unique architecture to their advantage

- The attackers face the daunting task of assaulting a structure built to last centuries

- Each day of resistance buys time for potential reinforcements

The Tragic Aftermath

Despite their valiant efforts, the defenders ultimately surrender:

- In a shocking turn of events, 117 men are hanged the next day

- This act of brutality highlights the ruthless nature of the conflict

Legacy and Reflection

The siege of Ardmore offers valuable insights:

- It’s one of the earliest recorded military uses of a Round Tower

- The event marks a turning point in the local history of Ardmore

- It serves as a poignant reminder of Ireland’s complex and often violent past

As you stand before Ardmore’s Round Tower today, take a moment to reflect on the brave souls who once sought refuge within its walls. Their story, long overlooked, adds another layer of depth to this already remarkable monument.

Ardmore’s siege may be a footnote in history books, but it’s a chapter of Irish history written in stone – a testament to human resilience in the face of overwhelming odds.

Citations:

[1] https://www.ardmorewaterford.com/the-siege-of-ardmore-1642/

We include a second account of the The Round Tower of Ardmore, and its Siege in 1642 (January 1, 1856) as presented in The Journal of the Kilkenny and Southeast of Ireland Archaeological Society BY JOHN WINDELE, ESQ.

Amongst the manuscripts left by the late Thomas Crofton Croker — a name long and creditably connected with our legendary literature and folklore — was a collection of tracts relating to the Irish civil wars of 1641. These had been originally published at the period to which they relate but were become so scarce, that when accident placed them in his possession, despairing of procuring other copies, he undertook the task of transcribing them in his own clear and beautiful penmanship. On the dispersion of his library, this MS. was purchased by J. W. Hanna, Esq., of Downpatrick, to whose kindness I am indebted for their perusal, and the use of the following extract relating to Ardmore.

The main interest appertaining to this portion of the narrative arises from the fact of its being one of the very few notices which we have, of an older date than the last century, regarding our Round Towers. It will to be sure, throw no light whatsoever on the origin or early history of that of Ardmore, for it merely relates to an incident in its otherwise uneventful history, belonging to a very gloomy period in the annals of Ireland. But it will serve as a landmark in the dim obscure of a structure concerning which another story there is none. The siege of Ardmore tower and castle, which forms its subject, was a circumstance, in the miserable civil war of the period, which our historians have thought too insignificant to notice, and of which, therefore, it is well thus to preserve the memory. The narrative tells in what a fell spirit that warfare was carried on, when, at its close, we are informed that the unhappy garrison, part of which had failed in defending the mysterious and time-hallowed old structure, having surrendered ” at mercy,” one hundred and seventeen of them were hanged the next day — in cold blood.

The castle which sustained its share in the tragic episode lay to the east of the church. Its “stump” was standing in 1745, in Smith’s time, but all vestiges of it have since then long disappeared.

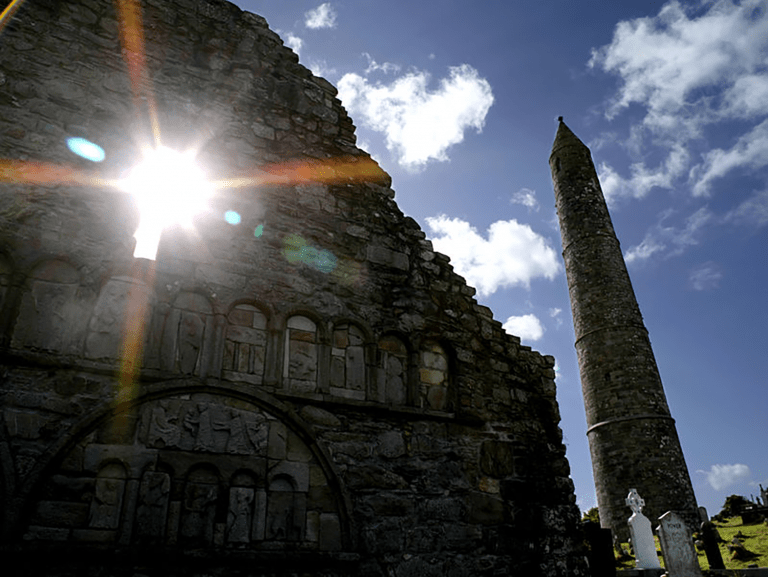

The tower here called the “steeple,” stands to the south of the old cathedral church of St. Declan. It is based upon the solid rock, which approaches within a few inches of the surface. It is certainly the most remarkable of that class of monuments, the crux of antiquaries — the Round Tower — so peculiar in Western Europe to the Gaelic family of the great Celtic race, possessing characteristics distinguishing it from other structures of the same type in Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. Its careful and highly finished masonry, its succession of external string courses or offsets, and those strange, sculptured, corbel-like stones, studding the face of its lower stories, single it out, with that of Devenish, as the very idea of these structures. Ardmore also enjoys the distinction of having been the first tower whose examination disclosed the very important fact, at first strenuously questioned, but now sufficiently established by researches, with similar results, in other buildings, that these structures had been raised for a sepulchral purpose, apart from other uses, whereby, also, the true object of the great elevation of their doors above the surrounding level is now satisfactorily explained.

The description of this tower by Smith, the historian of Waterford, is in many respects erroneous, as in the number of its string courses, 4 instead of 3; height, 100 feet, instead of 97; door, 15 feet from the ground, instead of 1 3, &c. He mentions three pieces of oak remaining in his time, near the top, ” on which the bell was hung,” as also ” two channels cut in the cill of the door, where the rope came out, the ringer standing below the door, without side.” In 1841, when Mr. Odell restored the long-absent wooden floors, the pieces of oak, mentioned by Smith, were found to have been joists belonging to the two upper original floors, one of which is now preserved in the Cork Institution; and the channels in the door sill area, with more probability, judged to have been formed as rests for the ladder, a purpose to which they have been now again applied. Indeed, had the bell-ringer ever chosen to exercise his function in the open air, it is not likely that the friction of ropes could have ever produced those indentations.

The sculptured corbels, so-called, which so strangely occur on the wall within, have been conjectured as intended for supports to shelves, on which were placed the precious things of the tower; but this is far from probable, inasmuch as they are only found in this and, perhaps, the tower of Rattoo in Kerry, and here, several of them are incapable of sustaining any object upon them; moreover, no two happen to be placed inline, so as to support a shelf.

It forms no part of the object of this communication to enter upon the debatable topics connected with the Round Tower question, which, although several very complacently consider as “settled,” it is hardly necessary to say, is deemed to be still in a very unsettled state by a large section of Irish archeologists. But in regard to the immediate structure under notice, as the opportunity offers, it may be permitted briefly to advert to one or two subjects particularly pertinent to it. One of these is the name of the locality on which the tower and its accompanying structures stand, about which there has been some small controversy. According to the Life of St. Declan, it was anciently called Ard na gcaerach; what alias it may have had besides, we are not informed; but Irish topography was rich in a variety of denominations. The present general name is Ardmore, but the particular or sub-denominations are Ardo, Ar do-chesty, and Ardoguinagh. The Ordnance Map is rightly in accordance with these popular designations. Yet Dr. Petrie denies that the tower stands on the land of Ardo. It is, he says, “situated on the glebe of Ardmore,” and so it is, for the glebe of Ardmore forms part of Ardo, but the exigencies of his anti-ignicolic theory will not let him see this. True, Ardo may not mean the tire height at all, for has a variety of significations, one of which is a yew tree. But why select this rather than a salmon, an ear, a grave, a peg, a pin, a nail, a bodkin, a thorn, &c? (see O’Reilly). Be its meanings ever so numerous and variant, the word Aodh, pronounced eo, significant of fire, or a fire temple, has a legitimate right to a place, and the more so, as the many Pagan indications in the vicinity so fully warrant its propriety. Here are a holed stone, or dolmen; on the shore, a cairn; a rock basin within a few yards of the tower, once honoured with the circular dance; a holy well; remarkable traditional vestiges of bovine or arkite worship in the rian bo Padruic, or roadway of St. Patrick’s cow; the cairn of the red ox; the fas an aon oidhche (growth of one night) attributed to the tower; the deisiol rounds performed at its base, &c, &c. ; and the remarkable accumulation of Ogham inscriptions.

These are collateral circumstances, giving great weight to the ” fire height” interpretation.

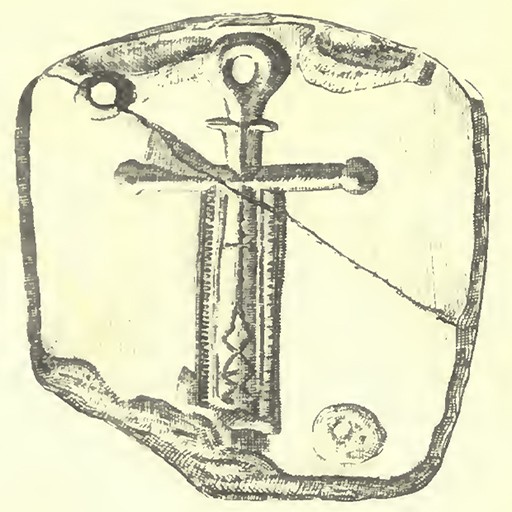

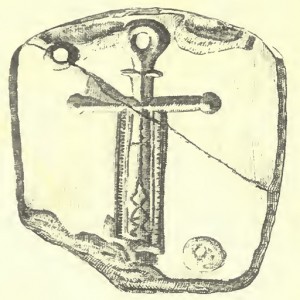

But Dr. Petrie denies that the discovery of an Ogham inscription can in any way affect the question at issue regarding the Bound Tower, for he thinks the Druidical origin of the Ogham writing remains to be proved, and to this denial and opinion he emphatically adds, in reference to the first inscription discovered here by me in 1841 : — ” I utterly deny that the lines on the stone at Ardmore are a literary inscription of any kind, and I challenge Mr. Windele to support his assertion by proof.” To this peremptory challenge, the best and only answer was given which it was capable of receiving: an engraving of the stone was made and circulated (a reduced copy of which Mr. Fitzgerald has since published in vol. iii., p. 227, first series), and the stone itself was shortly afterwards forwarded to the Boyal Irish Academy, where it still remains. For the Druidical use of Ogham, Dr. Petrie’s own work (pages 105 and 106) affords evidence, at least, one should suppose, sufficient to satisfy him. In illustrating ” the modes of interment practised by the pagan Irish,” he quotes from “that most valuable MS., the Leabhar na h-Uidhre,” a passage describing the grave of Fothadh Airgtheach, monarch of Ireland, who was killed at the battle of OUarba, in

A.D. 285: — “There is a chest of stone about him in the earth,” says the extract, ” and there is a pillar stone at his earn, and an Ogumis (Ogham) inscribed on the end of the pillar stone which i’ in the earth, and what was in it is, Eochaid Airgtheach here.”

Of course, it is unnecessary to say that the date, 285, was anterior to the establishment of Christianity in Ireland. Many other such pillar stones, with inscriptions in the same character, have since been found : two have been discovered in the Ardmore burial ground, as the pages of these ” Proceedings” record. One of these, embedded in the original masonry of probably the most ancient

Christian structure in this island, shows, from its position, that its object, use, and value had been forgotten, and become obsolete when that building was erected — perhaps in the fifth century.

The character of the majority of our Ogham inscribed monuments is undoubtedly Pagan. Comparing their inscriptions with those in the Romanesque Irish letter, still remaining at Lismore, Scattery, Aran, Clonmacnoise, &c, there is a marked and radical diiference; all the latter inscriptions observe a given formula, beginning almost invariably with or, or oroit do, i.e. ” pray for,” a form altogether absent in the Ogham. This most significant fact is, of itself, sufficient to satisfy an unprejudiced inquirer. Dr. Petrie, however, does not appear to have been so clearly convinced upon this head. Yet not so as to the genuineness of the inscription, for,

in his reply to the explanation given, he candidly avows his mistake. As the readers of his work cannot be cognizant of this fact, I may be excused for extracting from a letter to me, dated 21st October, 1845, a passage expressive of his regret for its commission: — ” I have,” he says, ” to request your pardon for the trouble which I thoughtlessly put you to in the matter of the Ogham inscription at Ardmore. I assure you with sincerity that I am very sorry for it, as taking it as certain that the marks in the stone are faithfully copied, and have no hesitation in acknowledging that it is a true Ogham, and shall state this and make the amende in the second volume of my work.” Eleven years having since elapsed, and the promised volume conveying the necessary amende not having yet appeared, I trust I may not be deemed unreasonable or premature in entering into these particulars here. To the large number of

Dr. Petrie’s readers and admirers, and of the latter, indeed, I avow myself one in all sincerity, the challenge remains on record, apparently still unanswered, and probably may be regarded as unanswerable; the occasion afforded in presenting the story of the Ardmore siege appears, therefore, to me sufficiently opportune for placing

1 Mr. Edward Clibborn, Assistant Secretary pressed his knowledge of it in his printed tary, Royal Irish Academy, in his letter to circular, published with a woodcut.” It may Mr. Odell, printed in vol. iii., p. 283, first be satisfactory to this querist to know that series, has very pointedly put the following — so far from suppressing my knowledge of query to that gentleman : — ” How is it that it — I did not see the stone in question until Mr. Windele has not noticed this” (the Ora- last November, just ten years after that cirtory stone) V ” He appears to have supcular had been issued. the subject in its right aspect before our Society, and so far vindicating my own judgment regarding this inscription impeached in the passage referred to.

I have already stated that the history of Ardmore tower before is a blank. The tradition of its having been built in one night, like that regarding so many of the cavern temples of India, affords but faint light indeed. Its vernacular name of Guilcach or Cuilcach Dhiaglain, is equally inexpressive. It is true that Dr. Petrie says this term is obviously a local corruption of Cloigtheach ; but this is very far from being so certain. Guilcach or Guilce is a very distinct native term, signifying a reed, and may be applied figuratively to these tall, slender, and taper columns; but, even were it another form of Cloigtheach, as he contends, this, with him important term, no more signifies a Round Tower than it does a square steeple, or any stone building of any form, low or lofty ; and this the learned Doctor, after all his laborious parade of examples and quotation, is himself virtually compelled to admit See pages 367 and 390 of his work. It is clear enough, generally speaking, that it signifies a steeple of some kind, and so Colgan and O’Conor and others very properly consider it ; but it is an egregious error to regard it as solely signifying a Round Tower. When, therefore, we read of the cloictheach of Armagh, or Slane, or Trim, or Tomgrany, where no remains now appear, we ought to be informed upon what evidence we should regard these buildings as round or angular, high or low.

It results from these observations, that Ardmore affords no positive fact, beyond the very important one of the discovery of its sepulchral character, to guide the inquirer, and that its era and other uses belong still to the speculative antiquary to seek out. It is only with the record of its siege in 1642 that its real history commences.

The life of the great patron saint of Ardmore is silent upon it, affording a negative evidence that neither he nor his successors for, probably, some ages after (for the life is a production of a later time), raised this structure. Hanmer the chronicler, who lived at Youghal, within four miles of Ardmore, is also silent regarding it.

From 1642 until Smith wrote in 1745, Ardmore remained unnoticed; since then it has been more or less referred to. But the great events in its history have been the restorations, the repairs, and the excavations effected in 1842, in a spirit and taste worthy of all laudation and imitation, by Mr. Odell, the now lord of the soil — himself a travelled, enlightened, and zealous archaeologist. Following upon these notable incidents have been the discoveries of the two additional Ogham inscribed stones, one that of the Monachan, by Mr. Fitzgerald, and the other, if I mistake not, by Arch-deacon Cotton — a name of grateful memory to every Irish antiquary, for what he has accomplished at Cashel and otherwise.

To hold so large a number as forty men, it is evident that the floors of the Tower must have been perfect, in 1642, and the presumption thence arises that this building had been, to that time, in use, it may be, as a belfry. The injuries inflicted on the church upon that occasion may also, very probably, have originated its subsequent disuse, desertion, and ruin. During the last century the chancel was again restored, as a place of worship, to be again unroofed and abandoned upon the erection of a new church in its neighbourhood in recent years.

The narrative of the siege of Ardmore Castle and Round Tower is extracted from ” A Journall of the most Memorable Passages in Ireland, Especially that Victorious Battell at Munster, beginning the 26 of August 1642, and continued. Wherein is related the Seige of Ardmore Castle together with a true and perfect Description of the famous Battell of Liscarroll. Written by a worthy Gentleman who was present at both these Services. London,

Printed for T. S. October 19, 1642:” and is as follows :—

” After the Irish had gathered together the greatest part of their forces about Killmallocke with intention to passe the mountainss into the County of Corke, and found they should receive opposition by our Army, which was drawne up to Duneraile and Mallo, with resolution to encounter them if they once descended into the Plaines, they again retreated towards Limmericke, and we about the 20 of August, Disbanded and went to our severall Garrisons, both with like intentions of gathering the Harvest of the Country. Sir John Paulets and Sir “William Ogles Eegiments went to Corke and Kingsale, the Old Eegiment was Garrisoned about Duneraile, part of Sir Charles Vavasors lay at Mallo, the rest that went to Youghall were commanded to obey the Lords Dungarvan and Broghils, who having procured a Culverine to be sent along with them, resolved as soone as our men were refreshed after their March, to take in the Castle of Ardmore.

The Fort is of its own nature, strong and defensible, it was well manned with 100 able Souldiers besides the people of the Countrey, it had munition sufficient, so we expected not to gain it, but after a long Seige. Not-withstanding it being a place of good consequence affording the Enemy meanes of getting the Harvest on that side in security, and blocking us up in Piltowne and Youghall, so that a man durst not appeare on the other side of the River, we resolved the taking of it, and upon Friday being the 26 of August, we marched from Lismore towards the Castle.

Our Forces were about 400 all Musketts, besides 60 Horse, part of the two Lords Troopes, by the way we summoned the Castle of Clogh Ballydonus which promised to yeeld and receive our Garrison, if M r Fitzgerard of Dromany would permit; we were satisfied with the answer, Mr. Fitzgerard being yet our Friend and the place being of no great importance, so that it was not thought convenient to lose time there, but Marched away and sate down before Ardmore. The same day about three of the Clocke in the afternoone we summoned it, but they not admitting of a Parley, we Quartered ourselves about the Castle, expecting our Culverine, which we sent down by water. In the meane time our men possessed themselves of some outhouses, belonging to the Castle, whereby we with more security might play upon the Enemies Spikes, and they in the evening fired the rest. All the begining of the night they played from the Castle very hotly upon us, but neverthelesse we ran up & tooke the Church from them, so that now we were within Pistoll shot of the Castle; this did much advantage us, for besides provision, whereof there was a good quantity, the Church standing high, beate into their Bawne, so that from hence they lost the use of it, and were forced to containe themselves with the Walls of the Castle. There was yet the Steeple of the Church, something dis-joynd from the body of it, yet remaining, which was well manned. Powder and bulletts they had sufficient, but wanted guns, there being no more than two Muskets onely among forty men, the Church cut off” all hope of supplies from them, so that we were confident to have it surrendered either for want of prouision or Ammunition. Thus we spent that night; next morning there appeared about 100 Horse and 300 Foote of the Enemy, and it was generally believed there was a more considerable number following ; we received the Alarme with joy and courage, and leaving onely sufficient to continue the Siege, drew forth the rest of our men, resolving to encounter them; but as our men advanced, they retreated towards Dungarvan, our Horse could not follow by reason of a Glinne betwixt us and them, and our Foot would have beene too slow to overtake theirs. We returned therefore to our Quarters, where we received intelligence from Mallo, that all the Enemies

Forces were againe drawne into a Body, and upon their march towards Duneraile, whereupon we were commanded to be at an houres warning; this troubled us onely because we feared we should raise the Seiges, and now more then ever we wished for our great Artillery, which came about noone to us ; and such diligence we used, that before three of the clock, we drew it up within halfe Musket shot of the Castle, and there planted it, though they played upon us all the way both from the Castle and Steeple, which we so carefully avoyded by wooll packes we carryed before us, that there was not one man shot in that service.

“We placed our piece to mine one of the Flankers, first, but when it was ready to play, the Castle desired a Parley, wherein they asked Quarter for goods and life, but that being denyed, they were content to submit themselves to the mercy of the Lords, who gave the Women and Children their cloathes, lives, and liberty to depart; the men we kept prisoners.

“All this while the Steeple held out, nor would they yeild untill they had conferred with their Captaine, after which they submitted to mercy.

“In the Castle were found 114 able men besides 183 Women and Children, 22 pound of Powder, and Bullets answerable, in the Steeple were only 40 men who had about 12 pound of powder and shot enough.

The next day we hanged 117. The English prisoners we freed, the rest we kept for exchange of such of ours as were with the Enemy.

“Thus was the Castle delivered unto us after one days Seige onely, wherein we lost not a man. The next day we left a Guard of 40 men in the Castle and marched away to our several Garrisons, expecting further command from our Generall which we received upon Wednesday being the last of August.”