Nestled in the heart of Ardmore, County Waterford, St. Declan’s Cathedral is a magnificent testament to Ireland’s rich ecclesiastical history. This awe-inspiring structure, steeped in legend and lore, invites visitors to explore its ancient stones and discover the stories that echo through the ages.

A Sacred Foundation

The cathedral is built on the site of St. Declan’s original monastery, founded in the 5th century. Recognized as a cathedral in 1170, it has been a focal point of Christian worship for centuries. The current structure showcases a fascinating blend of architectural styles, reflecting various phases of construction that have taken place over the years.

Architectural Marvels

As you approach St. Declan’s Cathedral, you’ll be captivated by its unique features:

- Chancel and Nave: The oldest part of the cathedral, dating back to the 9th century, is the chancel, while the nave showcases late 12th-century craftsmanship.

- Sculptured Arcade: The west wall features an extraordinary series of sculptures that depict biblical stories, including scenes of Adam and Eve and the Judgment of Solomon. These intricate carvings tell tales that have fascinated visitors for generations.

- Ogham Stones: Inside, you’ll find two ogham-inscribed pillar stones—ancient markers that glimpse Ireland’s early writing systems.

A Rich Tapestry of History

St. Declan’s Cathedral is not just an architectural gem; it’s a treasure trove of history:

- The cathedral has witnessed significant events throughout Irish ecclesiastical history, including debates about the timeline of St. Declan’s mission compared to that of St. Patrick.

- The Waterford & South East Of Ireland Archaeological Society has extensively documented its historical significance, emphasizing its role in shaping Ardmore’s identity.

The Legacy of St. Declan

St. Declan himself is a figure shrouded in mystery and reverence. As one of Ireland’s earliest saints, he is believed to have brought Christianity to this region long before St. Patrick arrived. His legacy endures in the cathedral and the surrounding landscape, where sites like St. Declan’s Well and Declan’s Stone continue to draw pilgrims and visitors alike.

Visiting St. Declan’s Cathedral Today

When you step inside this hallowed space, take a moment to absorb its serene atmosphere:

- Explore the Nave: Admire the beautiful Romanesque windows illuminating the interior with soft light.

- Reflect on History: Imagine the generations of worshippers gathered here for prayer and celebration.

- Capture the Moment: The stunning architecture provides countless opportunities for photography, so don’t forget your camera!

Plan Your Visit

Whether you’re a history buff, an architecture enthusiast, or simply seeking a peaceful retreat, St. Declan’s Cathedral offers an unforgettable experience. As you wander through its ancient halls and admire its intricate details, you’ll immerse yourself in a story spanning centuries.

Conclusion

St. Declan’s Cathedral is more than just a building; it is a living testament to Ireland’s spiritual heritage and cultural identity. As you explore Ardmore, let this magnificent cathedral inspire you with its tales of faith, resilience, and community spirit.

Come visit St. Declan’s Cathedral—where history comes alive!

Citations:

[1] https://www.ardmorewaterford.com/st-declans-catherdral/

There are many reasons to come and stay in Ardmore.

But, in essence, the unique combination of people, place, and heritage naturally lend themselves to being part of Ireland’s Ancient East.

Ardmore’s impressive heritage areas range from the Round Tower to St Declan’s Well to something as unique as St Declan’s Stone.

But for many, the site of Ardmore Cathedral stands out as being steeped in a rich cultural heritage – a land of saints and scholars.

Ardmore Cathedral is located on the site of St. Declans Monastery and was formally recognised as a Cathedral in 1170. A Recorded Monument it was first constructed by Meolettrim O Duibh-rathra sometime before he died in 1203.

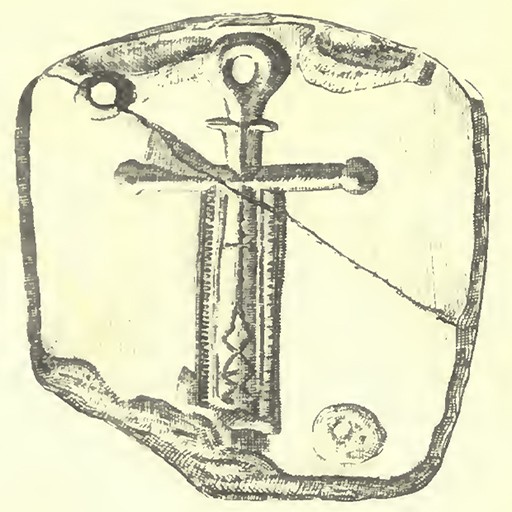

It has undergone several phases of construction over the centuries and the present building is of various periods and styles. The chancel is the oldest part of the cathedral dating from the 9th century, with the nave being late 12th-century work. Further works on the south side-wall and the east gable are of the 14th century. The most unusual feature is the arcade – a series of sculptures on the outside of the west wall telling stories from the bible. Many of the upper panels are worn, but you can just make out the Archangel Michael weighing the souls.

Included in the lower panels are Adam and Eve, the Adoration of the Magi, and the Judgment of Solomon.

The Waterford & South East Of Ireland Archaeological Society (1898) discussed Ardmore Cathedral at length:

Around Ardmore and its venerated founder centered one of the much-vexed questions of Irish ecclesiastical history, viz. – the date of St. Declan’s mission. The question is now, thanks to the scholarly labours of Dr. Todd, practically set at rest. Instead of a predecessor of the National Apostle, as Dr. Lanigan and his school would make St. Declan, the latter is now more generally regarded as the 6th century contemporary of St. David of Wales. But this is merely by the way. Our immediate concern is not with disputed questions of’ ‘chronology but with the remains still existing at Ardmore. The latter comprise the Cathedral and its Round Tower, the primitive oratory known as “Relig Deglain,” or St. Declan’s Grave, and the church by the cliff, commonly called Dysert Church. To the foregoing-list of monuments ought to be added the Holy Well near the ruin last mentioned and St. Declan’s Stone on the beach beneath the village.

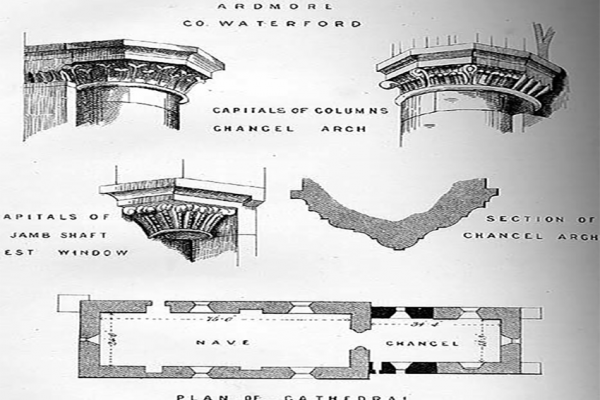

The Cathedral – This is the most important archaeologically, as well as the most interesting architecturally, the remains enumerated. It consists of a nave and choir separated by a very beautiful and very early pointed arch. Almost every phase of ancient Irish architecture is represented in this church. The oldest portion is to be sought for in the choir, on the north exterior of which masonry of almost Cyclopean character can be examined. Probably this belonged to the original choirless church of St, Declan, which was modified previous to the middle of the 12th century by being embodied in the present ruined cathedral. As portions of the north and south side walls of the choir are the oldest features in the church, so the choir arch and the east window, now built up, and the recessed tombs in the nave are the most modern. The arch, of late 12th or early 13th-century character, is well-deserving of detailed study. The thrust is resisted by ponderous sandstone piers 2 feet 3 inches in diameter. Remarkably high bases (56 inches) from which the columns spring, and the lightness of the arch above, lend to the whole arch an appearance of massiveness and grace respectively. The moulding of the archivolt is very elaborate, and the capitals of the piers are richly sculptured with lotus bud ornament.

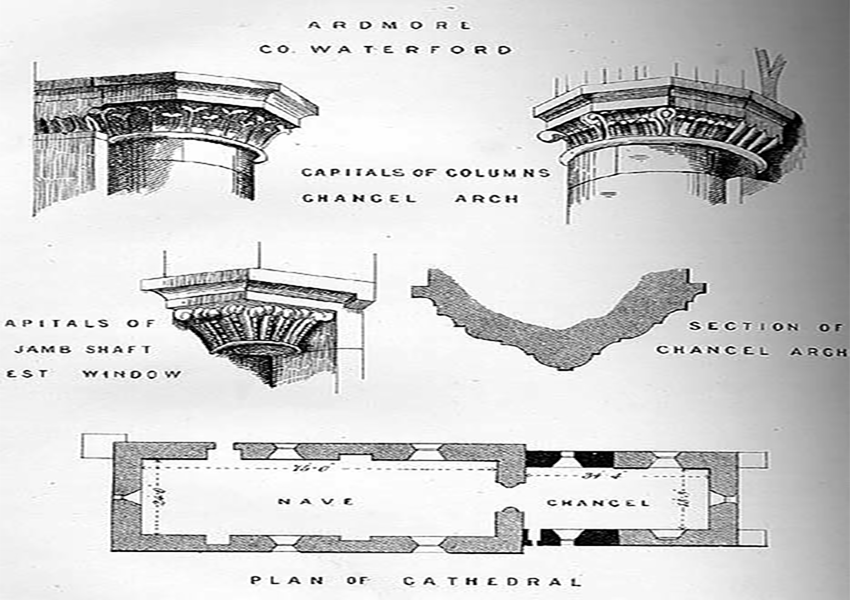

Standing within the choir the visitor will not fail to notice ‘ the two ogham inscribed pillar stones in the north-west and south-west angles respectively. One of them was discovered built into the eastern gable of the little oratory known as Relig Deglain. A third ogham stone, now in the National Museum, was found built into the nave wall of the cathedral.

The nave measures 72 feet 2 inches in length, 25 feet 9 inches wide, and its sidewalls are 17 feet in height. It was lighted from the sides by four 11th century Romanesque windows in addition to a beautiful but now, alas, disfigured Celtic window in the West gable. Details and indeed measurements of all five windows vary so that no two are duplicates. There were two entrances-both at the sides-but the south doorway is now closed up by masonry. The north doorway was of two or three orders, but the columns have all been destroyed. A small section of a broken column with lozenge ornament, now preserved within the nave, will give an idea of the wealth of decoration lavished on this doorway and on the now forlorn west window.

The feature which perhaps will most engross the visitor’s attention – as it is indeed the most extraordinary feature of the ruin is the arcading of the nave. Arcading, though a common characteristic of Romanesque churches on the continent is comparatively rare in Irish churches of the same date. The best-known examples of arcading in Ireland are Kilmalkedar (Co. Kerry), Cormac’s Chapel, and Ardmore. In the case of Cormac’s Chapel, the arcades are both internal and external, rounded and highly ornate, while at Kilmalkedar the arcading is internal only and the panels square. Here at Ardmore the arcades are internal and external, the panels are square, round-headed, and pointed, and the spaces instead of being blank and silent as at Kilmalkedar and Cormac’s Chapel, are most of them filled in with mystic, allegorical and. historic figures, which tell a story yet remaining to be read in full. The accompanying illustration of the external arcading is from the writer’s negative; it renders elaborate description unnecessary. Unfortunately, the figures are very much worn; in some instances, they are so defaced as to be perceptible only to the sense of touch. These external arcades are in two courses or storeys, of which the lower comprises two large semicircular spaces enclosed in a moulding string course, The upper storey consists of thirteen smaller round-headed compartments. Each of the lower and larger spaces is 4 feet in height on the clear, while the smaller arcades above vary from 2 feet 8 1/2 inches by 18 inches to 2 feet 6 3/4 inches by 15% inches. The left or northern arcade of the lower course is subdivided into three smaller spaces, which contain figures representing respectively a horseman mounted, the Temptation of our first parents and a bishop blessing a warrior, who, with uplifted lance, kneels before him; the last is conjectured to represent the conversion of the pagan prince of the Desi. The Temptation is in the conventional Celtic style, as on the great cross of Durrow, the cross of Drumcliff, Co. Sligo, &c. Within the right or southern panel, which is subdivided into six spaces, we have-above, the Judgment of Solomon and below, the Dedication of the Temple (III Kings, viii).

In the smaller panels, the round arches spring from long slender shafts, each with its capital aid base. The middle panel is the engraving indicates, is appreciably larger than the other panels of the row. Beginning with the panel to the extreme left the subjects appear to be:-

1 and 2. Now empty.

3. Much worn figure of thresher (?) with flail (perhaps Gideon)

4. Bishop (presumably) seated and imposing hands-on inclined and kneeling figure before him.

5. Two tall figures, much worn. Hindermost figure has a hand extended so as to touch the shoulder of a similar figure in front.

6. Figure of bishop with right hand raised and partly broken; left-hand holds a crozier, head outwards. The abnormal size of the crozier is remarkable.

7. Large figure of bishop holding in his right hand an object which reaches to the height of his head and seems to rest against the latter. On the left, he holds a second object, with a triangular (V) shaped head. To the right of the bishop is a kneeling figure, presenting a chalice or drinking vessel.

8. Figure (somewhat broken) of bishop with crozier in left hand.

9. Three skeleton-like figures in line and above the three other similar figures surmounted by a single figure of like type.

10. Suspended scales representing the Particular Judgment. Out of one side, two figures hang, while one of the other a single figure is suspended.

11. Seated figure of king or bishop. A kneeling figure before him offers something which he holds with elevated hands.

12 and 13. Now blank.

Coming next to the internal arcades, which are confined to the north wall of the nave, we find that they are of two kinds – square and pointed. The square-headed panels break the wall space between the door and the first window; they are five in number and measure each about 28 1/2 inches by 22 inches. Commencing about 12 inches beyond the first window the pointed arcades, twelve in number, extend along the wall choirwards. The spaces vary slightly in size-the general measurements being 49 by 23 inches.

Seven early medieval tombstones of thick slate-some of them cross inscribed lie on the floor of the nave. Unfortunately, not a letter of the original inscriptions (if they ever bore any) is now visible. The plain but graceful Hiberno-Romanesque windows of the nave, the trefoil tomb recess in the same compartment, and the comparatively modern and enormous external buttresses will all claim and no doubt receive their due share of the intelligent visitor’s attention.

Our church, the choir at least of which was in use till quite recently, bases its claim to the title of cathedral on the fact that there were bishops of Ardmore at various dates from the 6th to the middle of the 12th century. From this, however, it is not to be concluded that Ardmore was a regular diocese in our modern acceptance of the term. The ancient Celtic discipline as regards – the consecration and jurisdiction of bishops differed materially in many respects, be it remembered, both from our modern discipline and the ancient contemporary discipline of the Continental churches.

Episcopal jurisdiction in Ireland was largely monastic and tribal.

Owing to its singularly isolated position the Irish Church was slow to recognise, and equally slow to adapt itself, to the evolution of discipline and ritual which was taking place on the Continent; hence its many seeming anomalies and actual peculiarities.

[…] For further information on the cathedral, take a look at ardmorewaterford.com. […]