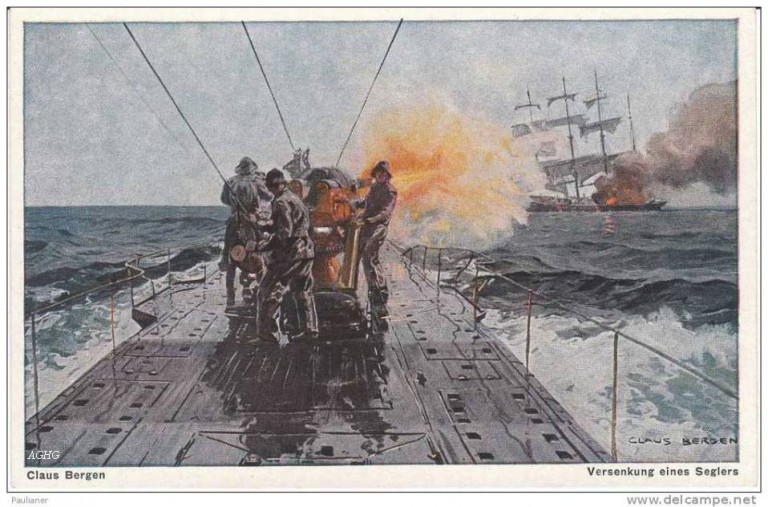

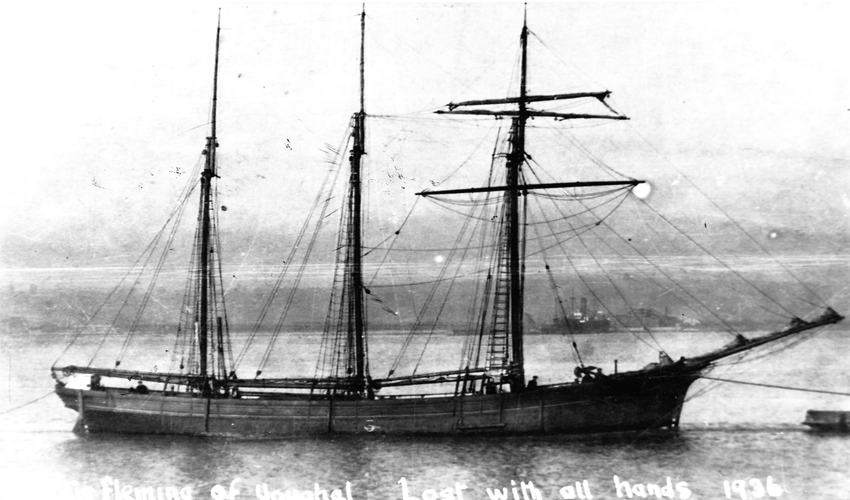

On a fateful day in December 1912, the Marechal de Noailles embarked on an extraordinary journey. This French vessel, hailing from the port of Nantes, set sail from Glasgow with an ambitious destination: New Caledonia, a French penal colony nestled in the South Pacific.

The Ill-Fated Voyage

The ship’s cargo hold was filled with a diverse array of goods:

- Coal

- Coke

- Limestone

- Railway materials

Aboard the vessel were 23 souls, including the captain, first and second mates, and a crew of 20.

A Journey Plagued by Setbacks

From the outset, the Marechal de Noailles faced numerous challenges:

- A week-long delay in Greenock due to inclement weather

- 17 days spent off Aran Island, Scotland

- A failed attempt to navigate the Irish Sea, forcing a retreat to Belfast Lough

The Final, Fateful Night

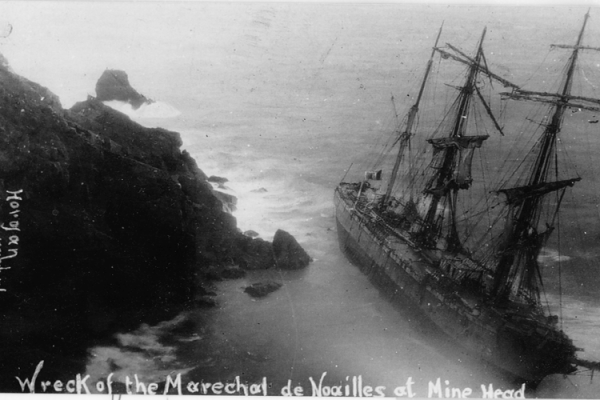

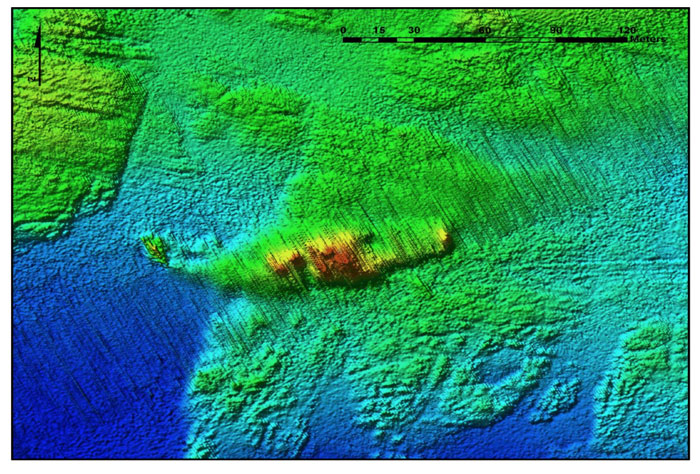

As the ship finally made headway, disaster struck near Ballycotton. The strengthening winds forced the captain to turn back, firing distress signals as the situation grew dire. Ultimately, the unforgiving sea drove the Marechal de Noailles ashore, just 300 yards west of Mine Head.

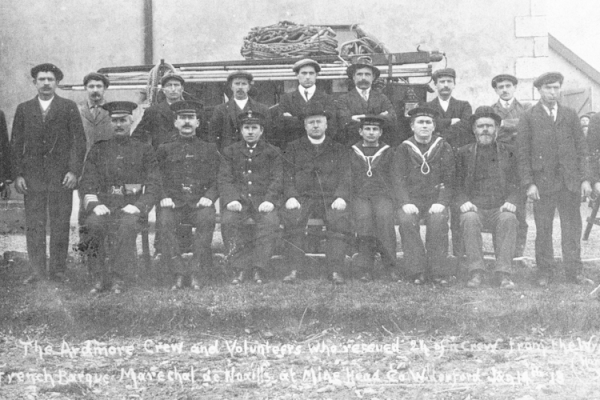

The Rescue Effort

The response to the ship’s distress was swift and heroic:

- Helvick Lifeboat attempted a rescue but was unable to approach the stranded vessel

- Mr. Murphy, the Mine Head lighthouse keeper, alerted the Ardmore Coastguards

- A dedicated rocket crew assembled, including Coastguards Barry and Neal, and local men such as J O’Brien, J Mansfield, and Fr. O’Shea

In a remarkable display of determination, the rescue team carried their apparatus on foot for 14 miles through treacherous conditions, arriving at the wreck site around 2 AM.

A Race Against Time

The rescue operation faced numerous challenges:

- The ship’s crew was unfamiliar with the rocket apparatus

- One sailor had been washed overboard

- Four crew members were unconscious and injured by flying spars

Through quick thinking and resourcefulness, J Quain used sign language to explain the workings of the rocket apparatus to the sailor who had been washed ashore. Using a megaphone, he instructed the remaining crew on operating the Breeches Buoy, enabling their safe evacuation.

Aftermath and Legacy

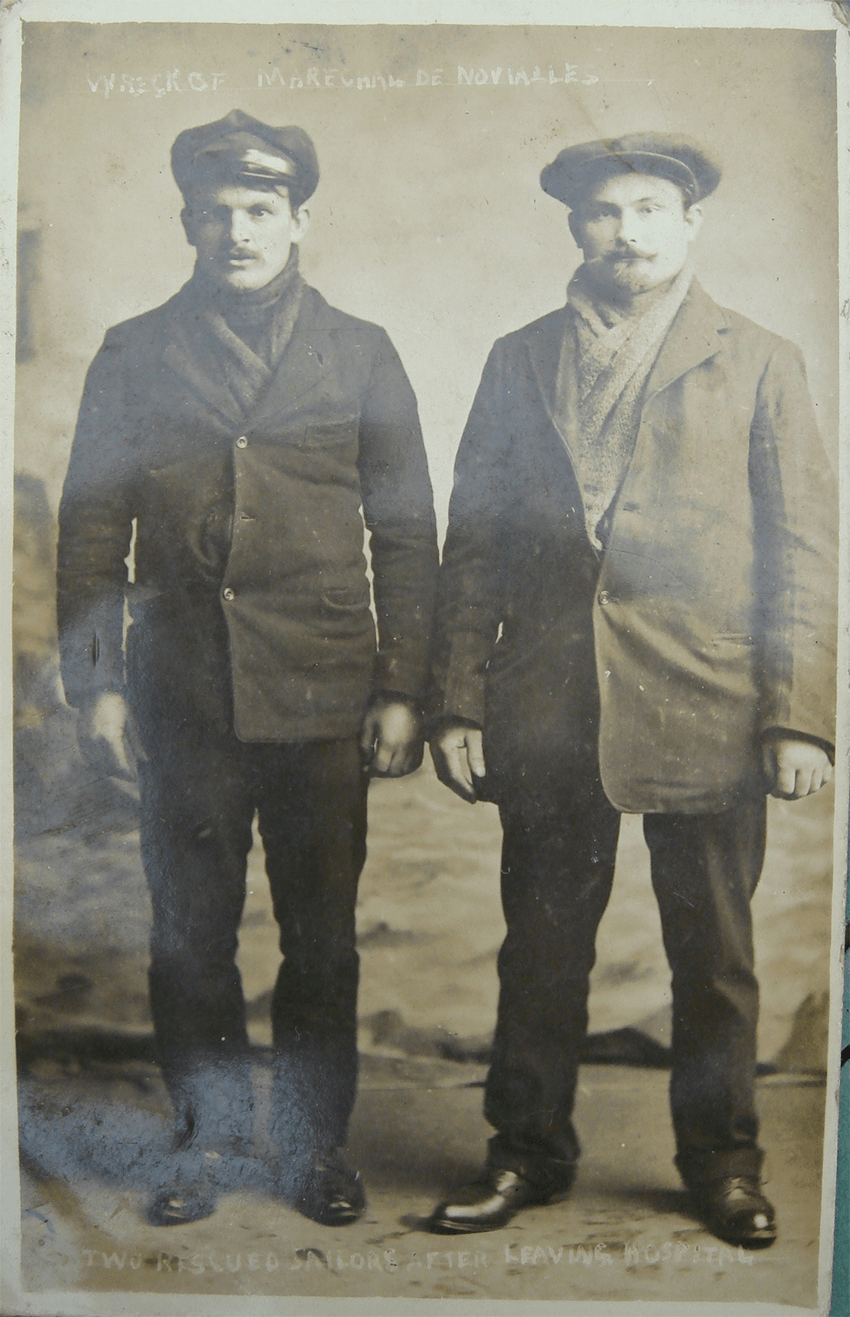

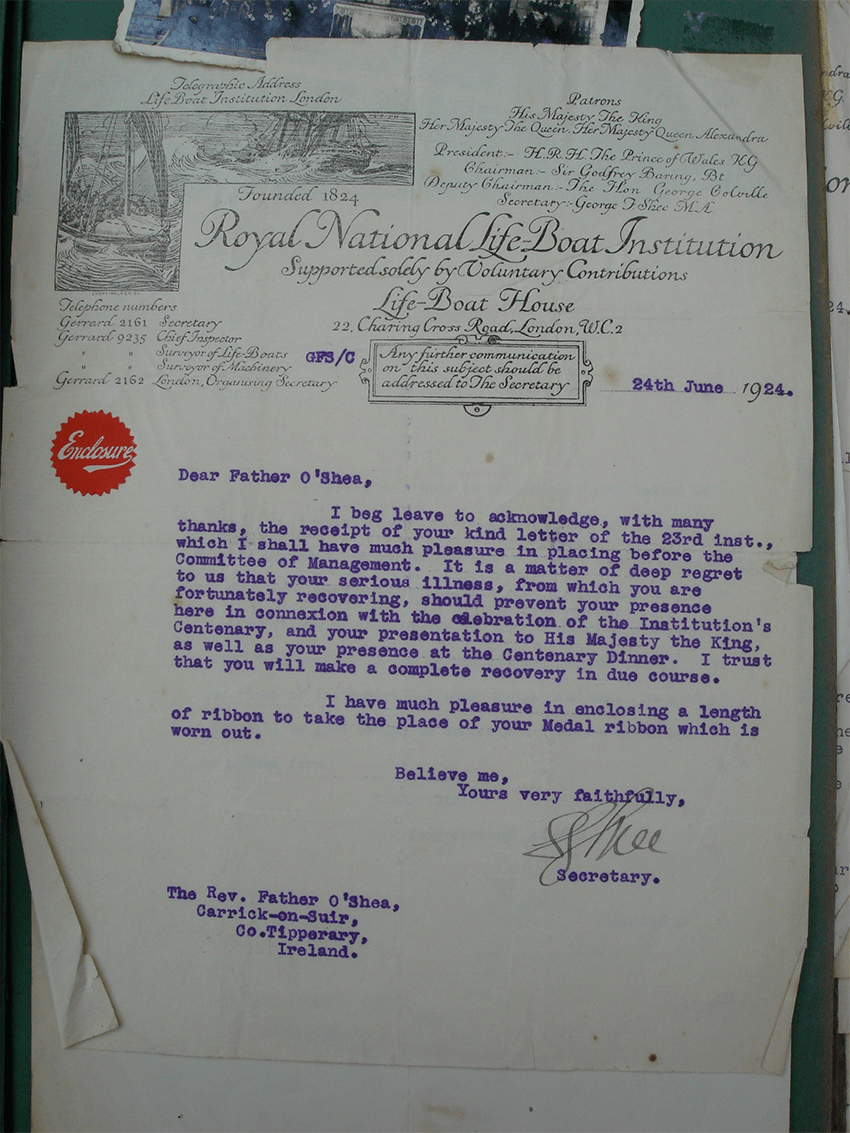

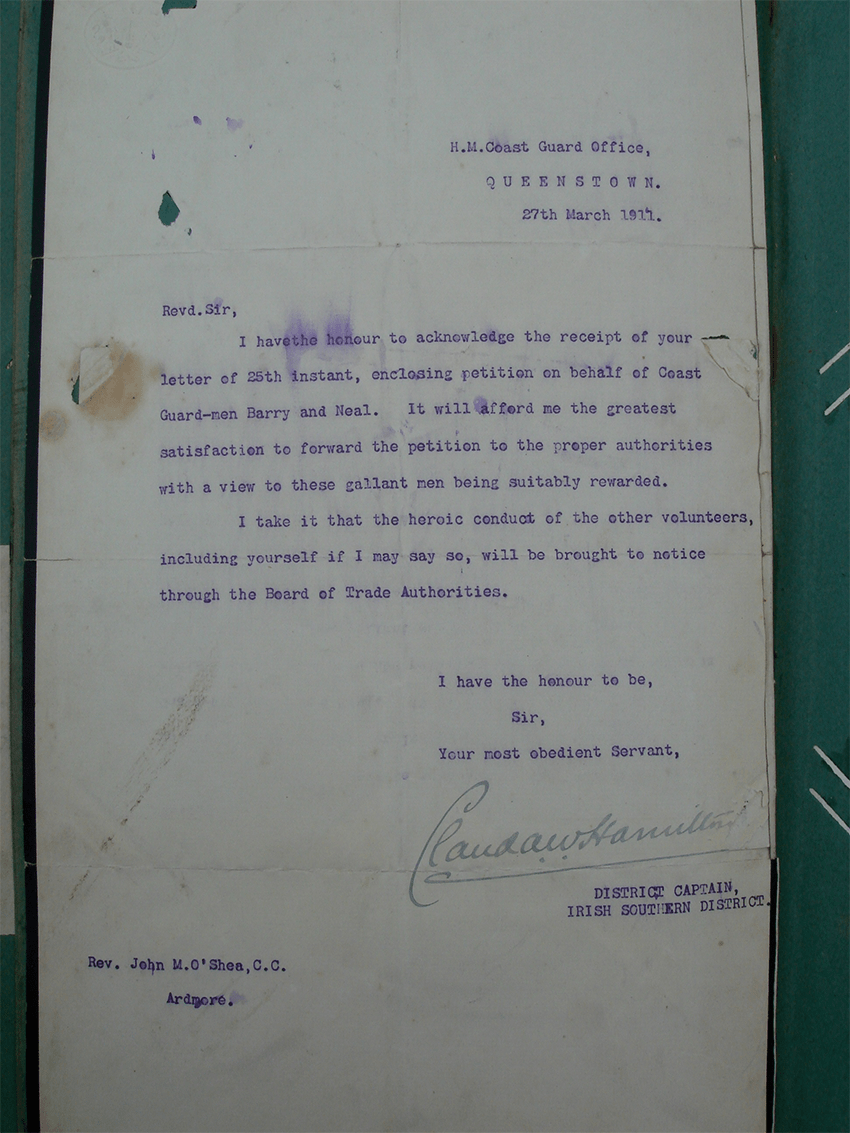

The rescued crew members were taken to Dungarvan for medical attention. Months later, Captain Huet from Morlaix sent a heartfelt letter of appreciation to Fr. O’Shea, underscoring the impact of the rescue effort.

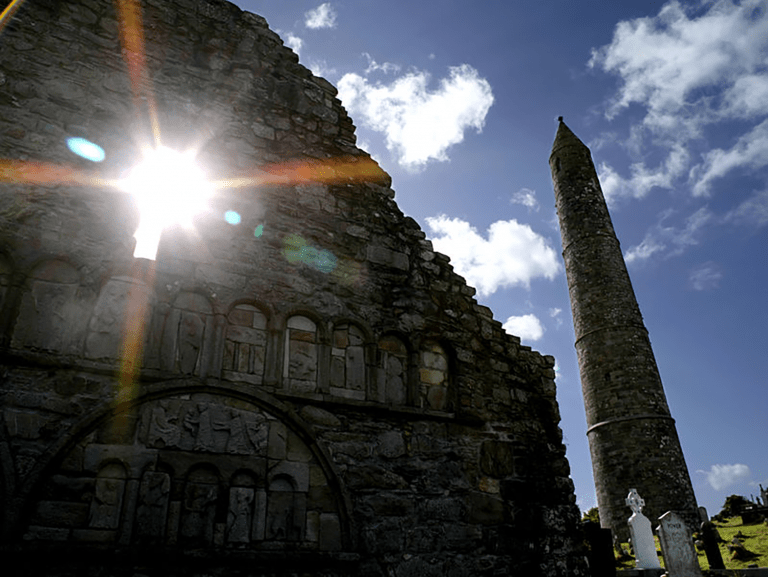

The Marechal de Noailles incident left an indelible mark on Ardmore’s history. The bravery of the local rescuers, who trudged through the night carrying heavy equipment, and their ingenuity in overcoming the language barrier ensured that this event would be remembered for generations to come.

Today, the story of the Marechal de Noailles stands as a testament to the indomitable spirit of seafarers and coastal communities, reminding us of the perils of the sea and the extraordinary acts of heroism they can inspire.

Most of the following accounts are taken from the article by Donal Walsh in Decies. September 1982.

The Marechal de Noailles of Nantes 12th December 1912.

On 12th December 1912, the Marechal de Noailles of Nantes left Glasgow for New Caledonia, a French Penal Island in the South Pacific. She carried a cargo of coal, coke, limestone, and railway materials. There was a crew of twenty besides the Captain and First and Second Mates. The beginning of the voyage was eventful with seven days being spent at Greenock waiting for an improvement in the weather; a further seventeen days off Aran Island, Scotland; then venturing down the Irish Sea but about sixty-five miles north of Tuskar having to retrace the voyage, this time to Belfast Lough. At last, they really got going and were a few miles from Ballycotton, when the wind strengthened. They turned about; the Captain fired distress signals; eventually, the ship was blown ashore three hundred yards west of Mine Head.

Helvick Lifeboat responded to the distress signals, but could not approach her. The keeper of Mine Head lighthouse, Mr. Murphy telephoned the Ardmore Coastguards, and the rocket crew assembled. Coastguards Barry and Neal, J O’Brien, J Mansfield, J McGrath, P Foley, J O’Grady, M Curran, J Quain, P Troy, M Flynn, Con Byron, Sergt Flaherty, Constable Walsh, and Fr. O’Shea.

As the roads were too bad for the rocket wagon to travel, the crew carried the apparatus fourteen miles on foot to the wreck and arrived about 2 am. The apparatus was assembled; the first rocket passed over the vessel, but the crew did not know how to deal with it.

Meanwhile, one sailor had been washed overboard and J Quain encountered him at the bottom of the cliff and explained the workings of the rocket apparatus, by sign language. With the aid of a megaphone, he instructed the rest of the crew still on the ship how to work the Breeches Buoy, and all the men came ashore.

Four had been injured during the night by flying spars and were unconscious and anointed by Fr. O’Shea. All were eventually taken to Dungarvan. Some months later, Fr. O’Shea had a most appreciative letter from Captain Huet, Morlaix.

No doubt, it was an unforgettable experience for the Ardmore men, tramping for hours in the dead of night with their apparatus which looked as if it wasn’t going to have the desired effect; then the joyful break-through the language barrier and being surrounded by a group of men “quacking like ducks” as one of them put it. So it is not surprising that the name Marechal de Noailles is remembered years afterward in Ardmore.