Step back to the 4th century A.D. and discover the enigmatic world of Ogham stones in Ardmore, County Waterford. These ancient relics, etched with Ireland’s earliest form of writing, offer a fascinating glimpse into our past and a tangible link to the legendary figures who shaped this historic landscape.

The Mysterious Ogham Alphabet

Imagine running your fingers along the edge of a standing stone, feeling the grooves and notches that make up the Ogham alphabet:

- A series of strokes along or across a central line

- Often called the “Celtic Tree Alphabet” due to its connection to ancient Irish tree names

- Used for around 500 years, primarily to commemorate important individuals

The Lugud’s Leacht: A Stone of Royal Significance

At the heart of Ardmore’s Ogham collection lies the intriguing Lugud’s Leacht:

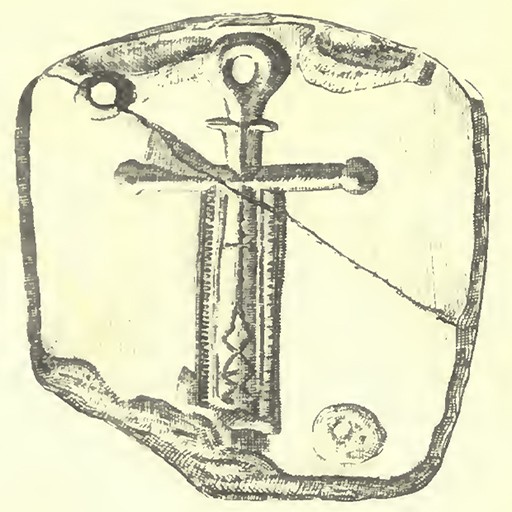

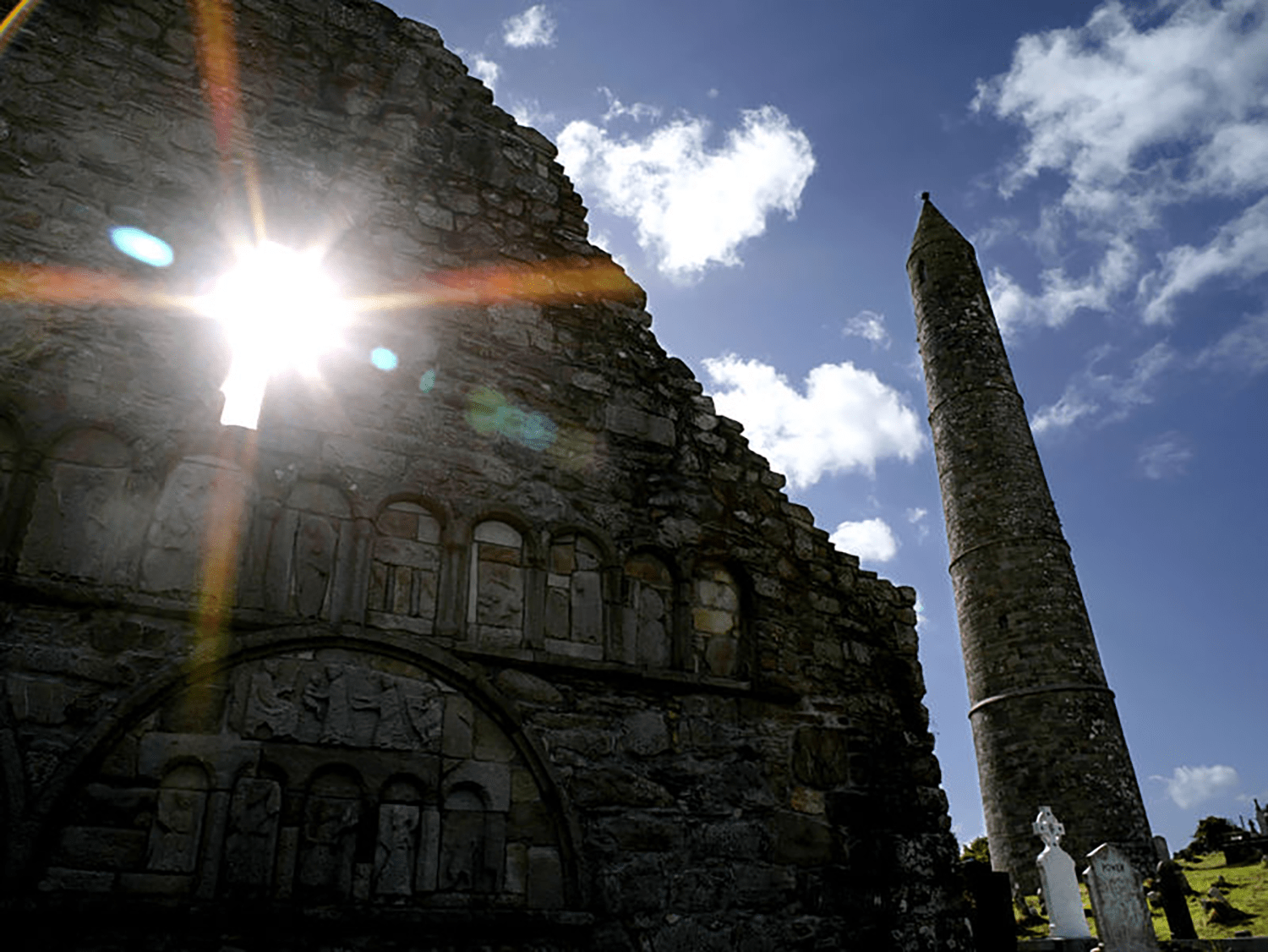

- Discovered built into the gable of St. Declan’s Oratory

- Bears the name “Lugud,” believed to be St. Declan’s great-grandfather

- Potentially dates back to the early 3rd century

The stone’s placement in the oratory wasn’t mere chance. It was likely a deliberate act to preserve this vital family relic, integrating pagan heritage with the Christian faith.

Deciphering Ancient Messages

The Lugud’s Leacht has sparked debate among scholars, with multiple translations offering different interpretations:

- One reading suggests: “Lugud, who died in his state of being head, lord, or chieftain”

- The inscription provides a rare glimpse into ancient Irish language structure and idioms

A Treasure Trove of Ogham in Ardmore

Beyond the Lugud’s Leacht, Ardmore Cathedral houses other remarkable Ogham stones:

- Each stone tells a unique story, waiting to be deciphered

- They stand as silent witnesses to Ardmore’s rich history and its place in Ireland’s Ancient East

As you explore these ancient treasures, let your imagination wander. Picture the skilled hands that carved these messages centuries ago and the stories they sought to preserve for eternity.

Ardmore’s Ogham stones are more than just archaeological curiosities – they’re a bridge to our past, inviting us to unravel the mysteries of ancient Ireland one stroke at a time.

Citations:

[1] https://www.ardmorewaterford.com/on-luguds-leacht/

Lugud’s Leacht And Amazing Ogham Stones

With fantastic itineraries, exciting places to go to, and must-see attractions, plan your perfect trip to Ardmore along Ireland’s Ancient East.

One must-see object you must see when you visit Ardmore is the Ogham Stones. These are located in Ardmore Cathedral.

Ogham is the earliest form of writing in Ireland. And it dates to around the 4th century A.D. It was in use for around 500 years.

And Ardmore has some great examples for you to explore.

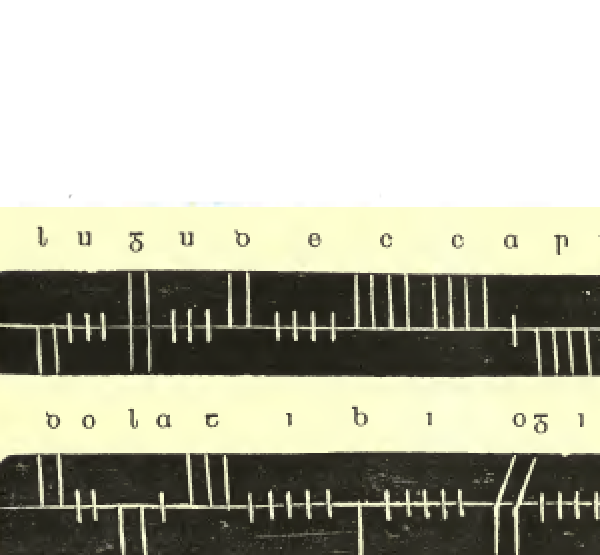

The Ogham alphabet comprises a series of strokes along or across a line. Often, Ogham is referred to as the “Celtic Tree Alphabet”. This is because a number of the letters are linked to old Irish names for certain trees.

The alphabet is usually carved on standing stones to commemorate someone, using the edge of the stone as the centre line.

The marks usually read from the left-hand side bottom up, across the top, and, if needed, down the other side.

We are pleased to present an article on the Ogham Stones of Ardmore as detailed in the Journal of the Kilkenny and the South East of Ireland (Volume III, 1860-61) written by E. Fitzgerald, Architect.

“THE antiquities of Ardmore have several times been brought under the attention of this Society; and an important point it will ever be found in archaeological pursuits, to note and publish jottings of discoveries and information as they are made and received; thus it has been to a considerable extent with regard to Ardmore, and with what effect will hereafter be seen. Somewhat cogent reasons have just now turned up, which, it is pleasing to know, give good grounds for identifying the Oratory Ogham at Ardmore with Lugud, the great grandfather of St. Declan, fixing the date of this inscription in the beginning of the third century. Being much interested in the antiquities of this venerable place, and especially in anything connected with the tutelar saint of the district, St. Declan, I was anxious for some time to get a translation made of his ancient MS. Life. With Mr. Windele’s assistance, I was enabled, about a year ago, to put it in a fair way of translation here; but translation and transcribing are slow work in the hands of a homy-handed peasant, after his hard day’s work is ended in the open air, even though a fair Irish scholar. Slowness will not suit some people, and the work was taken away from him when about one-third done, with a view to its completion by a much abler hand.

However, the portion translated included in it the pedigree of the saint, in which, on reading over, I was most agreeably surprised to find that LUGUD is there set down as the great grandfather of St. Declan, as the following extract from the manuscript shows:

Hence, it is to the race of Eoghan, the son of Fiacha Suighdhe, the natives of the Decies rightly belong, and of the race of the same Eoghan is the holy Bishop of whom, and of whose genealogy we write, namely, Declan, son of Ere, son of Trean, son of Lugud, son of Anac, son of Brian, son of Eoghan (the second), son of Art-Corb, son of Mogh-Corb, son of Muscraidhe, son of Mesfoire, son of Guana of the Just Judgments, son of Cura the Victorious, son of Cairbre the Long-handed, son of Eoghan (the first), son of Fiacha-Suighdhe, son of Feidhlimidh the Lawgiver, son of Tuathal the Legitimate, son of [Fiacha Finmolaidh, son of Feradach Fiun-fechlnach, son of Crimthan Niadh-Nairi, son of Lughaidh Sriabhndearg, son of Lothar (one of the * three Finns of Eamhan’) son of Eochaidh Feidhlioch, Ere, son of Trian, the father of Declan, was, moreover, King of the Decies.”

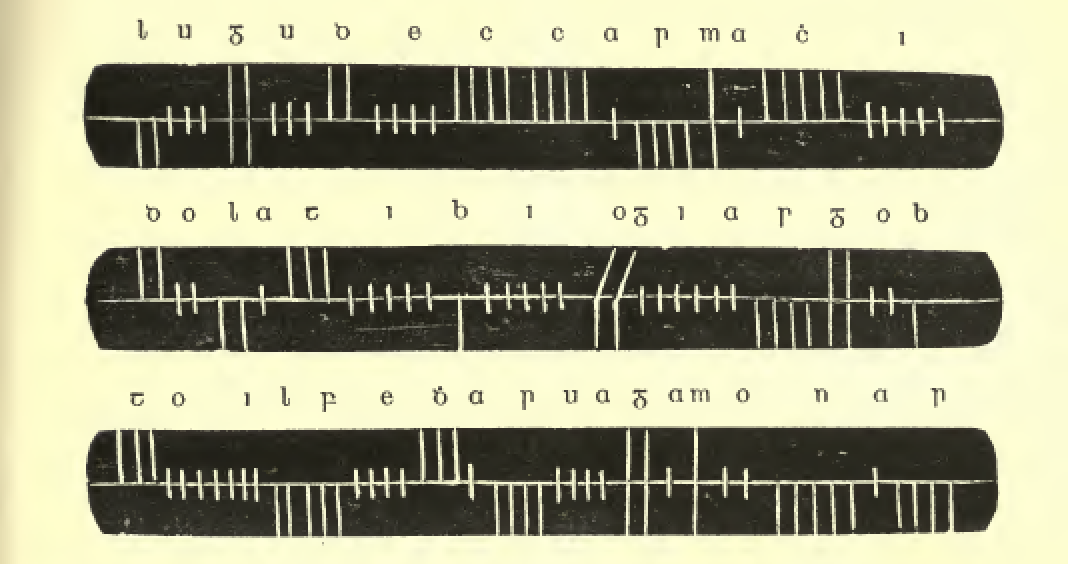

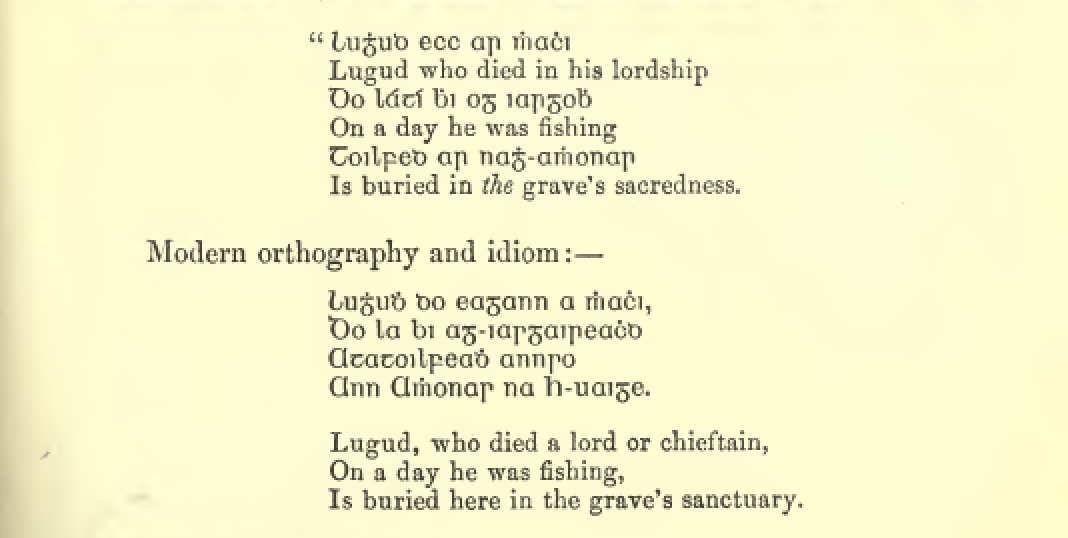

Drawings and translations of the Ogham inscription discovered in St. Declan’s Oratory have been published four times in this Journal: in vol. iii. p. 227, first series; vol. i. p. 45, new series; and at p. 330, same volume; also in vol. ii. p. 183. They were each given under different circumstances: the first, as the relic lay when discovered, built into the gable of the Oratory, the inscription being taken under considerable disadvantage, as the scores turned under and over the edges of the stone. The second was taken from a rubbing after the stone had been removed from the Oratory, and brought under closer inspection, and another line of inscription found on the back of it. The third was given, with a number of others, as readings of Ogham writings; and the fourth, with a number of Cryptic inscriptions from England. The four translations were from four different writers, Professor Connellan, Mr. Mr Windele, Williams, and the Rev. D. H. Haigh; and though each differed in their readings, yet all agreed that the name Lugud was inscribed on the monument. A misprint of one letter occurred in the name when first published, a G being substituted for an L in Lueud. which will at once be detected on reference.

I have got another reading of this inscription from Mr. Williams, which is of considerable importance in connexion with the present discovery, especially as he has good grounds for the alteration, from finding, on close inspection, that the letter i originally existed at the end of the first line, though now partly obliterated, the inscription originally appearing as follows:

“Maci” – I have met this word in several Oghams, used to mean a head or chief; an idiom peculiar to the Irish language occurs in this line, which it may be well to explain. Thus: if an Irish speaker or writer wanted to express the idea, John is king, he would use the words *acapeagan ann a pig,’ which our grammarians translate, ‘John is in his king.’ This form, however, does not fully express the sense of the Irish, which should be translated, John is in his state of being a King,

Hence, accordingly, the first line above literally signifies: Lugud, who died in his state of being head, lord, or chieftain.”

When this relic was discovered, an impression seemed general that it was built into the Oratory without more design than to use it as a common building stone. However, now finding the name Lugud to be a family name of St. Declan, and especially, as the first word to be read on the stone, as it originally lay in the Oratory, was Lugud, shows there was marked design in placing it in the building for preservation, and to be seen and read, as the principal part of the inscription was turned to the front.

On communicating my views on the foregoing to some of my friends, much interested in such matters, I was somewhat astonished to find them quite sceptical on the subject, saying, many other Luguds lived before that period, and why not identify this memorial with any of them, as well as with the great grandsire of St. Declan? Another great objection is, that a monumental pillar-stone, or leacht, should be made use of as a building stone in the erection of an Oratory, especially as a portion of the stone was broken off, so as not to interfere with the pitch of the roof such an appliance showing a contempt and disregard for the monument, not to be expected from the filial respect, affection, or reverence of the grandson or his friends. Now, as to the propriety of identifying this epitaph with Lugud, the great grandfather of St. Declan, in preference to any other, it seems clear and feasible to me : for where a memorial with a family name is found incorporated with and forming part of a private oratory, mausoleum, or vault of a prince, or celebrated man, from general usage, such name would be considered as of a connexion or near relative. But more especially, where we find that name set forth in the prince’s pedigree as that of his great grandfather’s, to my mind the conclusion of its identification is quite satisfactory. And as to the disrespect and irreverence, &c., &c., paid this memorial, by placing it in the building, I totally differ in opinion, considering that Declan or his disciples paid this Pagan monument the highest honour and respect in their power by incorporating it with the walls of one of the first Christian churches erected in Ireland, and have no doubt, from the position in which it was found, that it was for that purpose it was placed there. A portion of one end of the stone being broken to meet the incline of the roof, appears to me to be comparatively of late date, as by referring to the first sketch of this relic, published in vol. iii. p. 227, first series, it will at once be seen that, originally, at the left side, the gable rose considerably above the broken of part the stone, and that the breakage evidently was the work of a late period, probably when Bishop Mills re-roofed the building in 1716 as recorded by Ryland in his “History of Waterford,” for, of course, his workmen knew nothing of the inscription, and therefore set no value on the stone if it came in their way.

The next question is Is this “Life of St. Declan,” from which we have been qouting, an authentic ancient Irish manuscript? This question I must leave for our deep-read Irish scholars to decide; but this I may say, that Smith, in his “History of Waterford,” has quoted the MS. largely; and that Bishop Ussher published extracts from it as an ancient manuscript in his day, over two hundred years ago, and that the copy here used has been compiled from Irish MSS. in St. Isidore’s College, Rome, and at Louvain.”

Just wondering the relation between St Declan & St Coran Molana of Youghal?

Interesting article. I run a Ogham gift shop in Ireland which customise Ogham stones and framed artwork with the text of your choice. I would be grateful if you could post a link on your website to mine which sells these Irish gifts https://artymaniac.net/ogham-stone/