In 1895, the Journal of the Waterford and Southeast of Ireland Archaeological Society published a fascinating article by R. J. Ussher that delves into the discovery of a crannog in Ardmore, County Waterford. This insightful piece sheds light on the ancient structures that once dotted Ireland’s landscape and provides a glimpse into the lives of those who inhabited them.

What is a Crannog?

A crannog is an ancient dwelling typically constructed on stilts over water, often found in lakes or marshes. These structures were used as fortified homes, providing safety from invaders and wild animals. The construction involved driving wooden piles into the ground and weaving wattles between them to create a secure living space. The surface was then layered with timber, peat, and brambles, with a central hearth for cooking and warmth.

The Discovery in Ardmore

Ussher’s article recounts his discovery of a crannog in 1879 under unusual circumstances. The site was located just north of Ardmore village, where coastal erosion had dramatically altered the landscape. As the sea gradually encroached upon the land, remnants of the crannog were revealed beneath layers of peat and shingle.

Ussher described how he found the remains of this ancient structure exposed by the tides, noting that much of its upper surface had been washed away. Despite this, several intriguing artifacts were recovered from the site, including:

- A carved wooden handle, likely from a knife or spoon.

- A disc-shaped piece of wood with a hole in its center, possibly a lid for a churn.

- Iron tools, such as a hatchet and bill-hook.

- Animal bones, including those of red deer, oxen, goats, pigs, and donkeys—are common finds in crannogs that suggest dietary practices of the time.

The Significance of the Crannog

The crannog at Ardmore is significant not only for its archaeological value but also for what it reveals about early Irish life. Ussher posited that this structure must have originally been situated in a lagoon or marshland, protected from tidal influences. His observations indicated that centuries ago, Ardmore Bay was more extensive than it is today, likely enclosed by natural sandbanks.

The artifacts found at the site provide insight into daily life during its occupation—tools for crafting and cooking, evidence of animal husbandry, and hints at social organization within these communities.

The Impact of Erosion

Ussher lamented that due to rapid coastal erosion, much of what remained of the crannog had been lost to the sea. This ongoing erosion poses challenges for archaeologists studying similar sites along Ireland’s coastlines. The article serves as a poignant reminder of how environmental changes can threaten our understanding of history.

Conclusion

Exploring Ardmore’s crannog offers a fascinating glimpse into Ireland’s prehistoric past. R. J. Ussher’s 1895 article not only documents a crucial archaeological find but also highlights the need to preserve these historical sites against natural forces that threaten their existence.

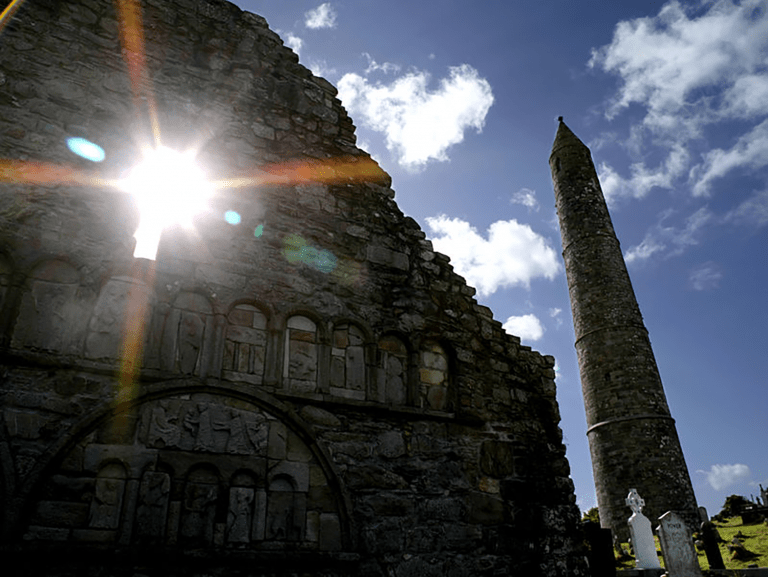

As you explore Ardmore today—home to stunning beaches, rich history, and vibrant culture—take a moment to reflect on its ancient past and the lives once lived on these now-submerged structures. The crannog is a testament to human ingenuity and resilience in adapting to their environment while leaving stories waiting to be uncovered by future generations.

Citations:

[1] https://www.ardmorewaterford.com/what-lies-beneath-ardmore-bay/

[2] https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/browse/details.xhtml?recordId=3039534

[3] https://sources.nli.ie/Record/PS_UR_095311/Details

[4] https://gedmartin.net/martinalia-mainmenu-3/374-nz-ardmore

[5] https://www.ardmorewaterford.com/crannog/

[6] https://www.jstor.org/stable/20651495

[7] https://heritageireland.ie/unguided-sites/ardmore-cathedral-round-tower-and-oratory/

[8] https://www.waterfordmuseum.ie/exhibit/web/Display/article/371/1/Ardmore_Memory_and_Story__The_Landed_Gentry_The_Odells.html

There’s A Lost Treasure In Ardmore Bay!!

Appearance can be deceptive.

At first glance, Ardmore Beach is like the other beautiful beaches along Ireland’s Ancient East.

Clean and crisp sands. It’s impossible not to be impressed.

But, when the tide is in, the sea seems to call us to share something more.

And, yes there’s a secret on Ardmore Beach.

But what lies beneath?

What has almost forgotten?

What has no heritage signpost?

And what is calling us?

There’s a spot just by the bend in the storm wall.

Right across from the Church.

It’s a section of the storm wall where you’ll see a kind of step. You’ll know the place when you see it.

After the mass, many “parliament” discussions take place there.

It’s easy to find.

Now, look out onto the sand towards Curragh. And, you see a section below where there was an old bog.

And, that’s where our very own Crannog once stood.

Want to know more?

We have a lovely article discussing this lost treasure in Ardmore Bay.

It was first printed in 1895 in Volume 1 of the Journal of the Waterford and Southeast of Ireland Archaeological Society.

It was written by R. J. Ussher.

Note to the visitor: The road to Dungarvan that he mentions below has been replaced, but it used to run parallel to the beach.

“The ordinary conditions of a crannoge, or stockaded island, are well known A small island or shoal was selected in a lake or marsh. A circle of oak piles was driven into it’; wattles were woven between these. The surface was heaped up with timber, peat, brambles, and other bulky materials. A heart of stones was constructed on the centre of the enclosure, and a wooden house was built here. Access was usually obtained by a canoe. The tribe or family lived in this isolated fortification and carried on all the arts of life known to them.

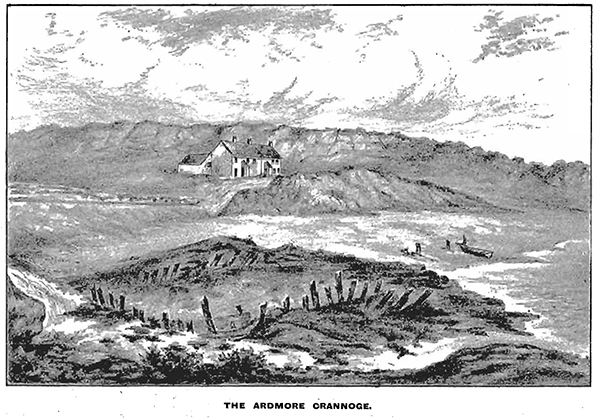

It fell to my lot to discover, in 1879, a crannoge under very peculiar circumstances. Its site is now covered by every tide. To the north of Ardmore village in this county the beach forty years ago ran approximately straight in a direction a little to the east of north, and the road to Dungarvan ran parallel to it. On leaving the village by this road one first crossed a small stream, beneath whose basin was an extensive bed of peat that ran out to low-water mark or beyond it. The road here traversed a great bank of shingle that had been piled by the sea upon the peat. Farther on the road rose upon a high bank of till, or boulder clay, which presented to the sea a high escarpment, Between the road and the escarpment stood a large schoolhouse and on the landward side of the road was a range of coastguard houses, Within my memory, the sea has devoured the land here so rapidly that, first the schoolhouse, then the road, and then the coastguard houses have been successively washed away. The great accumulation of shingle between the coastguard houses and Ardmore was also removed, its vestiges being now much further inland. A tract of the peat upon which the shingle had been piled was thus laid bare, and in this, I found the remains of the crannoge.

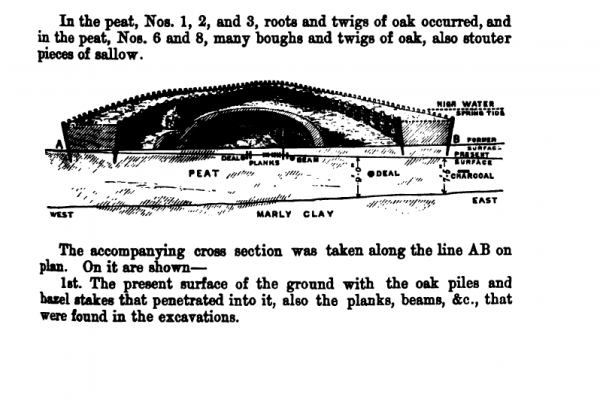

What took the eye was a double row of piles enclosing irregularly a space about ninety or a hundred feet in diameter. The upper ends of these piles had in most cases been broken, but the lower extremities, embedded in the peat from one to four feet deep, were all pointed as if by an axe. The piles in the outer circle sloped outwards and stood more closely together. Those in the inner row showed remains of having been wattled. A trench that I cut to a depth of nine ‘feet into the peat within the crannoge, showed that it was undisturbed without any artificial accumulation of materials such as were used to raise the surface of other crannoges. On the north-west side, the piles of the outer row were wanting, but twenty feet outside the remaining inner row of piles there lay embedded in the peat remains of a large piece of wattling, as though some of the walls or partitions had been torn down and thrown there. This wattling consisted of squared and unworked upright stakes (now prostrated), with long wattles woven’ between them in and out. Here in connection with this wattling, I found also embedded in the peat a piece of a beam of timber, cut off at one end, and having two mortices cut in it. The noticeable feature about this was that the rude cuts appeared to have been made by a stone celt, the rounded extremity of which had left its impressions on the cut surfaces. This mortised beam may have served for holding uprights or some other timbers of the crannoge structure. On the south-east side, I also found between the two rows of piles a piece of flooring or wattling composed of rods nearly as thick as one’s fingers and as close together.

These gave the impression that they were not in situ, but a piece of some structure that had got embedded there.

On examining the surface of the peat in the interior of the crannoge enclosure it was found to be studded with stakes, usually running in rows, which were broken off level with the surface from marine erosion. On digging some of them up their ends were found to have been pointed: Near the centre of the crannoge a large circle of these stakes could be partially traced, about twenty-six feet in diameter, and within this, I found standing upright in the peat two split boards of oak fitted tightly together. Their upper ends had been worn ‘or broken off, being exposed to wind and wave, but the lower ends sunk in the peat were cut off square. It seems that these planks belonged to a house of wood like that which existed in the Co. Fermanagh crannoges, described by Mr. Wakeman, and the rows of stakes represent wattled walls of dwellings or partitions within the crannoge fortification. The peat surface in this case afforded an admirable base for such wattled structures.

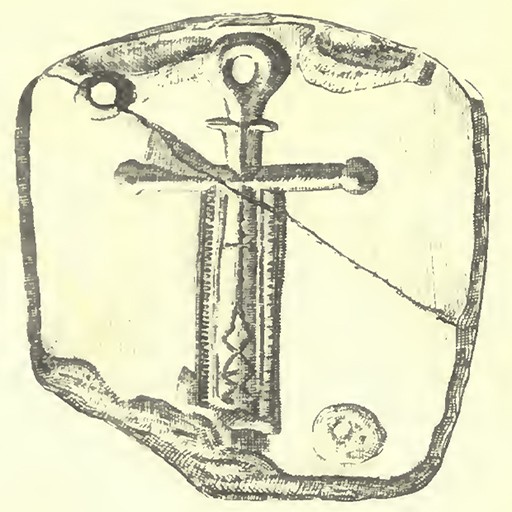

It is painfully evident that in 1879 so much of the upper surface of the peat and what it contained had been washed away that nothing but the bare foundations of the crannoge remained. Nevertheless, a few objects were found in connection with it. I took out of the peat on the east side, outside the enclosure, a carved wooden handle such as might have belonged to a knife or spoon, while an Ardmore man, named Shaughnessy, discovered also in the peat a disc-shaped piece of wood having a hole pierced through its centre, around which hole the wood was thicker than outside this portion. I at first took it for a wooden wheel, but it has been suggested that it was more probably‘ the lid of a churn. A horseshoe was also given me as having been found in the crannoge, having its internal margin shaped to suit the horse’s frog.

Others found there what they described as a hatchet and a bill-hook of iron, and Michael Foley, fisherman, when digging turf there, had found outside the crannoge, at a considerable depth in the white clay, what he called a cradle of green twigs, about four feet long, having a multitude of green leaves in it (leaves being wonderfully preserved in the peat). One can only conjecture that this may have been a wicker canoe.

In and around the crannoge many bones were found by myself and others embedded in the peat and stained of its dark colour. These were broken but not cut and represented the usual animals found in raths and crannoges, red deer, ox, goat, pig, and ass. At the present day, nearly all vestiges of the crannoge have been washed away by the rapid inroads of the sea.

What strikes one at first about the site of this crannoge is that it must have been formerly protected from the approach of the sea as well as elevated above the tidal level, for its present level below high-water mark would have been subject to flooding even in a marsh or lagoon at some distance from the sea.

That the crannoge must have been originally constructed in a lagoon or marsh seems obvious, such being the usual site for crannoges, and considering the rapid inroads that the sea has made within my own memory, it is reasonable to conclude that centuries ago Ardmore Bay was filled up to a much greater extent than recently, and a protecting sandbank may have enclosed its mouth, like the warren at Tramore or the Cunnigar at Dungarvan Bay, leaving inside a spacious lagoon or morass.

And we need not assume the subsidence of the whole coast-line to account for the crannoge having become depressed below the tidal level. The bed of peat on which it stood is now over ten feet thick in places. This is a highly compressible material and was once no doubt much thicker, its surface, on which the structure was built, having then been above the level of any tide.

What took place was probably this – the invading sea advancing towards it year after year brought along a great accumulation of shingle, such as I remember to have been heaped upon the spot forty years ago. The enormous weight of such a mass of stone would have been quite sufficient to compress the peat and sink it beneath the sea-level in time. The continuing advance of the sea, at last, removed the shingle itself and laid bare again the peat stratum and what remained of the crannoge.

I had the advantage of visiting Ardmore last year with Professor Boyd-Dawkins, and that eminent geologist countenanced the above views, stating that it was thus that the change had probably taken place. My earlier researches in the crannoge were guided by Mr. G. H. Kinahan, a veteran Irish geologist, whose previous knowledge of crannoges and powers of trained observation were invaluable to me.

The accompanying sketch of the crannoge was kindly taken in 1879 by Miss Blacker.”

We also include another article on the Crannog in Ardmore for your enjoyment