A chilling tale from Ireland’s tumultuous past lies in the peaceful coastal village of Ardmore, County Waterford. On a single day in August 1642, 117 men met a grim fate that would echo through the centuries.

The Siege Begins

Picture the scene: August 26, 1642. Lords Dungarvan and Broghill march towards Ardmore Castle with 400 musketeers and 60 horsemen. Their target: a formidable fortress housing 100 soldiers and numerous civilians[1].

As the sun sets, the attackers seize the nearby church, gaining a strategic vantage point. The defenders, now trapped between castle walls and enemy fire, face a dire situation[1].

A Desperate Stand

Inside the castle’s round tower, 40 brave souls mount a last-ditch defense. With only two muskets among them, they hold out against overwhelming odds[1].

The Fall

After just one day of siege, the castle surrenders. The victors offer a cruel mercy: women and children may leave with their clothes and lives, but the men face an uncertain fate[1].

A Tragic Aftermath

The next day, in a shocking act of brutality, 117 men are hanged. This mass execution stands as one of the darkest moments in Ardmore’s long history[1].

Echoes of the Past

Today, as visitors stroll Ardmore’s picturesque streets, few realize the weight of history beneath their feet. The castle and its tower have long since crumbled, but the memory of that fateful day in 1642 lingers on.

As you explore Ardmore’s ancient sites, from St. Declan’s Round Tower to the ruined cathedral, take a moment to reflect on the complex tapestry of Irish history – where tales of saints and scholars intertwine with those of siege and sorrow.

Citations:

[1] https://www.ardmorewaterford.com/117-hanged-in-ardmore-waterford/

117 Were Killed In Ardmore In One Day

What can you expect from a trip to Ardmore?

How about stunning landscapes, a temperate climate, a warm welcome, and a story of mass executions that will leave you speechless?

When we think of this peaceful place where we live and visit, it seems incredible to think that 117 people were hanged here on a single day.

How do we know this?

Well, because we have an eyewitness account from 1642.

Yes, you heard us correctly when we said an eyewitness account from 1642.

If you like to peel back the layers of history, then we know you’re going to love this account.

THE SIEGE OF ARDMORE CASTLE, 1642. BY JAMES BUCKLEY.

‘ Oh ! sadly shines the morning sun

On leaguer’d castle wall,

When bastion, tower and battlement,

Seem nodding to their fall.

The history of the County Waterford is particularly rich in interesting events relating to the period of the great civil war of 1641, principally on account of the vast importance of the city in those old days and of the many strong positions extending from the fort of Duncannon on one side to the ancient town of Youghal on the other. The present contribution is therefore intended as a continuation of those relating to the subject that appeared in last year’s volume of the Journal. It illustrates, to some extent at least, one of the most signal, but apparently little known of, events of the time in the political history of the county.

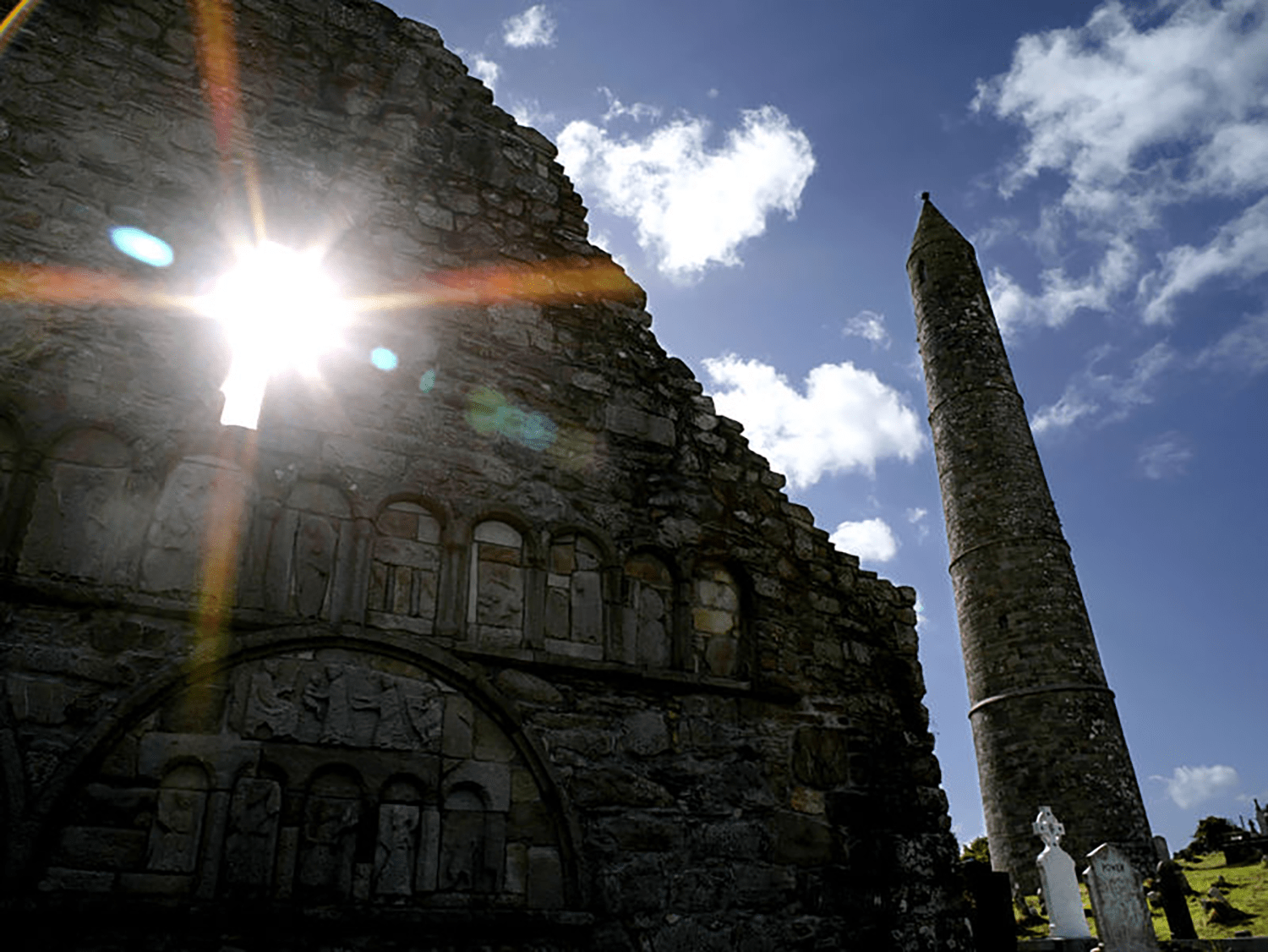

Owing to its many early Christian associations, all of which, generally speaking, have received a due meed of antiquarian attention, Ardmore possesses a story unrivalled for the quaint odour of its sanctity. Its interest is not even swallowed up in its ancient glory, as it can also recount a sort of second history – a history with which we are about to treat.

It would appear that there were two castles standing here at one time. Smith writing in 1746, records “Ardmore is now no more than a village, there apppears at present, the stump of a castle; and not long since, was a much larger one there, which was taken down. “The remains of these buildings were in existence as late as 1844, when Mr. O’Flanagan wrote his” Historical and Picturesque Guide to the Blackwater in Munster. “The author of that most useful and instructive work observes” There are also traces of two ancient castles, but neither history nor tradition throws any light on the persons by whom or the purposes for which they were erected. They had evidently completely vanished in 1860 when Hayman’s (Guide to Youghal, Ardmore and The Blackwater” appeared, as no mention of them is made therein.

With a view to inspecting what, if anything, remained of the original foundations and to obtaining a ground plan of them if possible, the writer paid a hasty visit to the locality one late afternoon last September and on inquiry from a most intelligent old man who takes care of the cemetry, as well as from personal observation was unsuccessful in identifying even the exact sites of the castles. However, considering the position of the church which evidently occupied higher ground than the besieged castle, as can be inferred from the account of the siege submitted hereafter, the latter building must have stood somewhere to the east of the round tower or steeple” as it is quaintly ycleped in the account referred to, and perhaps on a line with it and St. Declan’s oratory.

There is a small, narrow hollow in the ground immediately outside the churchyard and about 20 yards from the oratory in or near which the castle bawn or enclosure must have been, as the besieging party when possessed of the church were able to “beate into” it, and as at this distance, it would have been within musket range. On the other hand, had the castle stood on the north or west of the church it is impossible to conceive how those on the offensive side could have so easily wedged themselves into such a place of vantage.

Leaving these conjectures to themselves, we proceed to the siege of the castle. Writers on the civil war in Ireland are, to say the least of it, very sparing in their notices of the subject. Perhaps the brutal treatment extended to the garrison, after its having capitulated with a request for mercy, had no fascination for them, and that its dark story had been better left unwritten?

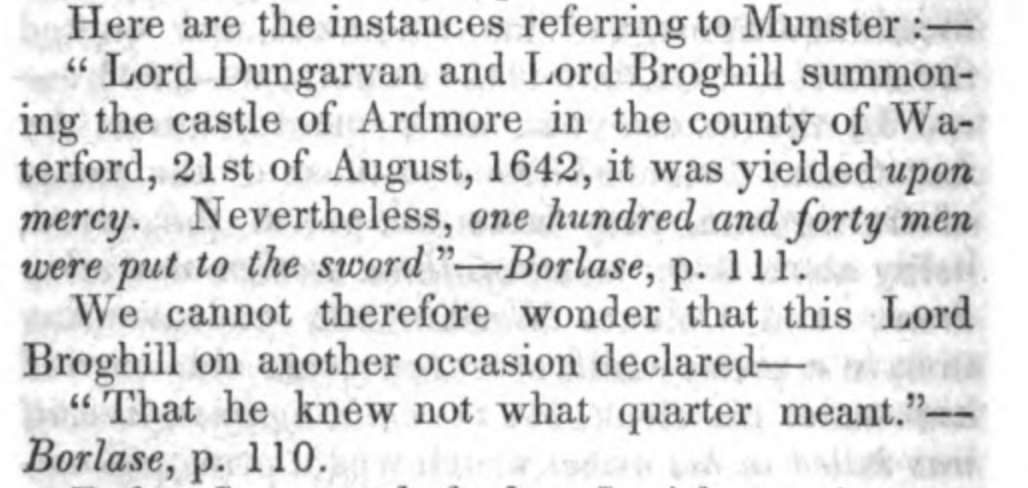

In his “History of the Irish Rebellion” Borlace having related how the Earl of Barrymore took in upon quarter the strong castle of Clogleagh in the County of Cork proceeds “Afterwards the Lord Dungarvan and the Lord Broghill, summoning [summoned] the Castle of Ardmore in the County of Waterford, belonging to the Bishop of Waterford, (and] after some petty boasts to withstand the utmost hazard it was yielded the 21st August 1642, on mercy, women, and children being spared, but a hundred and forty men were put to the sword, into which castle they afterward put a ward.” Carte in his “Life of Orrnond” and Smith our county historian, treat the matter with much more decency by completely ignoring it. Turning to the portly volumes of ” The Lismore Papers” disappointment again awaits us. The editor in his copious notes and illustrations” thereto, informs us The Diary hitherto kept with such regularity, now exhibits a hiatus for four months (May to August, 1642, both inclusive), We learn from other sources how a considerable portion of this time was filled by the Earl of Cork. As Custos Rotulorum of the Counties of Cork and Waterford and in obedience to the coinnlands of the Lords Justices of Ireland he held during the months of July and August Sessions Courts in the Guildhall of Youghal, for the indictment of the Munster rebels, and there he entered upon inquiries affecting the lives and properties of many chief nobles, gentry, as well as humbler classes of the province.’)

From these imperfect details, we come to the account of the siege to which allusion has already been made. A few observations concerning it may not be amiss. Some time since the writer accidentally came across a tract in the British Museum containing a very full and satisfactory account of the siege written at the time by an officer who took part therein. Each successive step in the engagement is described apparently as it occurred, and judging from the style and symmetry of the whole, it would appear to be the production of one accustomed to such work.

The following part of the tract comprising somewhat less than one-third of the whole relates exclusively to our present purpose.

“A Iournall of the most memorable passages in Ireland, especially that victorious battell at Munster, beginning the 26 of August, 1642,and continued.

“After the Irish had gathered together the greatest part of their forces about Kilmallocke, with intention to passe the mountaines into the County of Corke, and found they should receive opposition by our army, which was drawne up to Doneraile and Mallo, with resolution to encounter them, if they once descended into the plaines, they againe retreated towards Limericke, and we about the 20. of August, disbanded and went to our severall garrisons, both with like intentions of gathering the harvest of the countrey. Sir John Paulets, and Sir William Ogles regiments went to Corke, and, Kingsale, the old regiment was garrison’d about Doneraile, part of Sir Charles Vavasours lay at Mallo, the rest that went to Youghall were commanded to obey the Lords Dungarvan, and Broghils, who having procured a culverine to be sent along with them, resolved, as soone as our men were refreshed after their inarch, to take in the Castle of Ardmore. The Fort is of its owne nature, strong and defensible, it was well manned with 10o able soldiers besides the people of the countrey, it had munition sufficient, so we expected not to gaine it, but after a long siege.

Notwithstanding it being a place of good consequence affording the enemy means of getting the harvest on that side in security, and blocking us up in Piltowne (a) and Youghall, so that a man durst not appeare on the other part of the river, we resolved the taking of it, and upon Friday, being the 26. of August, we marched from Lismore, towards the castle. Our forces were about 400. All muskets, besides 60. horse, part of the two Lords troopes, by the way we summonecl the Castle of Clogh Ballydonus which promised to yeeld and receive our garrison, if Mr Fitzgerald of Dromany would permit; we were satisfied with the answer, Mr. Fitzgerald being yet our friend; and the place being of no great importance, so that it was not thought convenient to lose time there, but marched away and sate clown before Ardmore.

The same day about three of the clocke in the afternoone we summoned it, but they not admitting of a parley, we quartered ourselves about the castle, expecting our culverine which we sent downe by water. In the meane time our men possessed themselves of some out houses belonging to the castle, whereby we with more security might play upon the enemies spikes, and they in the evening fired the rest. All the beginning of the night they played from the castle very hotly upon us, but neverthlesse we ran up and tooke the church from them, so that now we were within pistoll shot of the castle; this did much advantage us, for besides provision, whereof there was good quantity, the church standing high beate into their bawne, so that from hence they lost the use of it, and were forced’ to containe themselves within the walls of the castle. There was yet the steeple of the church, something disjoyned from the body of it, yet remaining, which was well manned, powder and bullets they had sufficient, but wanted guns, there being no more than two muskets only among forty men the church cut off all hope of supplies from them ; so that we were confident to have it surrendered either for want of provision or ammunition.

[note (a) Pilltown, Where are the remains of a castle, once inhabited by the Walshe’s-Hayman, op. cit.]

Thus we spent that night; next morning there appeared about 100 horse and 300 foote of the enemy, and it was generally believed there was a more considerable number following; we received the alarme with joy and courage, and leaving only sufficient to continue the siege, drewforth the rest of our men, resolving to encounter them ; but as our men advanced, they retreated towards Dungarvan, our horse could not follow by reason of a glinne betwixt us and them, and our foot would have been too slow to overtake theirs. We returned therefore. to our quarters, where we received intelligence from Mallo, that all the enemies forces were againe drawne into a body, and upon their – march towaads Doneraile. Whereupon we were commanded to be at an hours warning: this troubled us, only because we feared we should raise the siege, and now more than ever we wished for our great artillery, which came about noone to us ; and such diligence – we used, that before three of the clock we drew it up within halfe musket shot of the castle, and there planted it, though they played upon us all the way both from the castle and steeple, which we so carefully avoyded by wooll-packes we carryed before us, that there was not one man shot in that service.

We placed our peece to ruine one of the flankers first, but when it was ready to play, the castle desired a parley, wherein they asked quarter for goods and life, but that being denyed, they were content to submit themselves to the mercy of the Lords, who gave the women and children their cloathes, lives, and liberty to depart, the men we kept prisoners.

“All this while the steeple held out, nor would they yeeld until they had conferred with their captaine, after which they submitted to mercy. (b)

(b) This is probably the first recorded instance of the siege of an Irish round tower. The taking of it does not strike one as being a particularly brave feat of aims, considering that it was defended with only two muskets.

In the castle were found 114 able men besides 183 women and children, 22 pound of powder, and bullets answerable ; in the steeple were only 40 men, who had about 12 pound of powder, and shot enough, The next day we hanged 117. The English prisoners we freed, (c)the rest we kept for exchange of ours’as were with the enemy.

Thus was this castle delivered unto us after one dayes siege only, wherein we lost not a man. The next day we left a guard of 40 men in the castle, and marched away to our severall garrisons, expecting further command from our generall, which we received upon Wednesday, being the last of August.”

In the ” Articles of Cessation of Armes” conclucled between Ormond and the Catholic Confederates on the 15th September, 1643, the following reference is made to Ardmore.

“And that . . . . the County of Waterford . . . shall during the said cessation remaine and be in the possession of the said Roman Catholique subjects now in Armes, and their party, Except Knockmorne, Ardmore, Piltowne, Cappoquin, Ballinetra, Stroncally, Lismore, Balliduffe, Lisfinny and Tallowe, all scituate in the County of Waterford, or as many of them as are possessed by His Majesties Protestant subjects, and their adherents.”

No further mention of the castle appears in connection with the long civil wars. It would seem to have bowed its stubborn head in peace as we read not of a battering cannon being directed against it.

Note (c). It is worthy of remark that the Irish prosecited the war in a civilized manner, In the present instance they had prisoners of war in their custody; yet certain writers discant largely on their iriassacres and wouId lead an ordinary reader to infer that cold murder was practised exclusively by them.

We include another article on this site which also discusses the Round Tower and it’s relationship to the siege of 1642.

We end this post with a short extract from A memoir on Ireland native and Saxon, by Daniel O’Connel M.P. (1883).

Very good account, but my goodness, hanging 117 men in one day! How horrific. I think of the women and children who were allowed to leave, knowing that their men would be killed and they’d never see them again. Likewise for the men: however relieved they were not to see their families slaughtered before them, they must have been heartsore knowing it was farewell forever.

Difficult to conceive that this was ‘normal’ practice.